“It is our fixed and

determined purpose to live and die on our present seats. It is sealed to us by

the bones of our fathers. They obtained it by their blood. Our bones shall be

beside theirs. It is the heritage of the Almighty. He gave it to us. He it is who

must take it from us.”

—Six

Nations to the President of the United States, 1818

Land Crisis: Erie Canal

Plans for the Erie Canal cut

right through the heart of Haudenosaunee lands. Where the Haudenosaunee saw a

living landscape that sustained their survival, New York politicians and

businessmen saw opportunities for development and the easiest route to the

West. An early canal proposal characterized the territory as “waste and

unappropriated lands” ripe for the state’s taking.

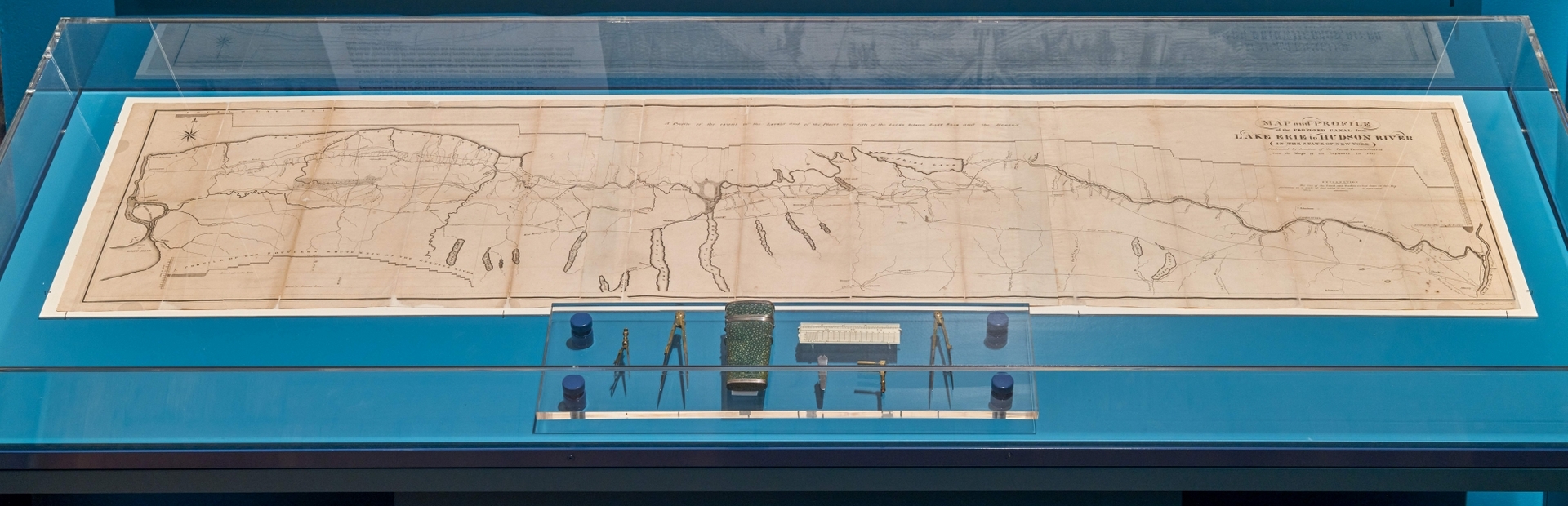

New York State Surveyor General

Simeon DeWitt used these surveying tools to plot the canal. Planners knew they

were boring through Native land. This map shows the canal winding through places

named after Haudenosaunee communities, including Onondaga Lake, Oneida Creek,

and the Seneca River.

In 1817, the Ogden Land

Company began construction. Supporters championed the canal as a sign of

American progress that would facilitate travel and commerce. Haudenosaunee

communities viewed it as a threat to their lands and ways of life. They

petitioned against private and public attempts to remove them from their homes

along the canal’s route.

Elias Valentine

Map and

profile of the proposed canal from Lake Erie to Hudson River in the State of

New York,

1817

Patricia D. Klingenstein Library, New-York

Historical Society

Surveyor’s kit owned by Simeon DeWitt

Albany Institute of History and Art, bequest of

Sarah Walsh DeWitt, 1924.1.21

Spiritual Crisis: Erie Canal

The land crisis sparked by

the Erie Canal precipitated a spiritual crisis for many Haudenosaunee people.

Which beliefs and practices would protect them? How could they sustain their

culture if they lost the places that anchored and shaped it?

To safeguard the

future of the Longhouse, people turned to several different sources of

spiritual power.

Traditional Practices

Red Jacket (1758–1830)

The Seneca leader Sagoyewatha

or Red Jacket defended traditional Haudenosaunee practices. He distrusted

Christian missionaries, regarding them as accomplices of the whites who were

stealing their lands.

His words to one New England

missionary were published in the broadside shown here. “You have got our

country but are not satisfied; you want to force your religion upon us. You say

there is but one way to worship and serve the Great Spirit. If there is but one

religion, why do you white people differ so much about it? Why not all agreed,

as you can all read the book?”

In 1819, the Ogden Land

Company met with Red Jacket and other Seneca leaders to pressure them into

selling land. Red Jacket spoke for the group when he refused, insisting that

all white men, including the preacher and schoolmaster, leave their

reservations.

Christianity

Reverend Eleazer Williams (1788–1858)

Protestant missionaries had

long worked among the Haudenosaunee. When the Erie Canal broke ground in the

center of the Oneida homeland, many Oneida Christians rallied around Eleazer

Williams, an Episcopalian missionary of Mohawk descent. Williams envisioned an

“Indian empire” in the West. He advised

his Oneida followers to migrate west in order to protect themselves from the

white population and practice Christianity how they saw fit. Between 1820 and

1838, about half of the Oneidas relocated to a new reservation near present-day

Green Bay, Wisconsin.

Williams preached captivating

sermons and enjoyed singing hymns—a mode of worship that resonated with

Indigenous traditions. He also contributed to this prayer book, which was

written in a “reformed Mohawk orthography” for speakers of Mohawk and Oneida.

Its contents include prayers, services, and thanksgivings drawn from the Book

of Common Prayer.

Protestant missionizing among

the Haudenosaunee continued even after most Oneidas moved west. These communion

vessels were used in a Presbyterian mission near the Allegany Seneca Nation

reservation.

Longhouse Philosophy

Handsome Lake (1735–1815)

In the summer of 1818,

spiritual revival swept through the Haudenosaunee council assembled at the

Tonawanda Seneca reservation. Years before, the Seneca prophet Handsome Lake

stood inside this same longhouse and preached a message of moral and social reform.

He revealed his visions in which the Creator sent instructions for revitalizing

Ongwehonweka:a, “the way of life of the original human beings.”

At the 1818 council,

followers of the late prophet revived Handsome Lake’s teachings to unite their

community. The book by a visiting Protestant minister displayed here documents

an oration from council participant John Sky, who “recapitulated the moral

truths delivered by the prophet.”

Handsome Lake’s Longhouse

philosophy of living sought to help adherents move forward despite poverty,

cultural disruption, and land loss. Some of his instructions overlapped with

the counsel of Christian missionaries, but he distinguished his Gaiwi:yo (“Good

Word”) from the Christian Gospel. His message emphasized longstanding beliefs

about the sanctity of family and the value of positive relationships,

generosity, and hospitality. It also sanctioned forms of worship important to

Haudenosaunee identity, including the Midwinter Ceremony, the Strawberry

Festival, and traditional thanksgiving dances.

Bridging Traditions

Caroline Gahano Parker Mt. Pleasant (ca. 1826–1892)

Caroline Parker was an artist

whose life bridged multiple spiritual traditions. Born Tonawanda Seneca and

married into the Tuscarora community, Parker followed prophet Handsome Lake’s

Longhouse philosophy and also was a member of the Tuscarora Baptist Church. She

balanced creative adaptations of Euro-American customs with the preservation of

her Haudenosaunee heritage.

Both influences are present

in Parker’s clothing designs. The outfit she wears in the photo—featuring this

skirt—takes the style of ceremonial Longhouse dress, even as additions like the

white lace collar reference contemporary Victorian fashions. The skirt’s “celestial

tree” motif is a quintessential Haudenosaunee pattern. Bold colors and symbolic

beadwork evoke the feminine powers of Sky Woman, a major figure in the

Haudenosaunee creation story. When worn during ceremonial dances, Parker’s

skirt became a “visual prayer” in motion.*

Caroline Parker’s textile art

illustrates how affiliating with Christianity did not necessarily mean losing

traditional spirituality or culture. Haudenosaunee peoples could adopt diverse

beliefs, philosophies, or perspectives and still remain united as inhabitants

of one Longhouse.

*Description from textile historian Deborah Holler

Threat to Potawatomi Homelands

The Erie Canal gave

Easterners a quick, easy route to the West. Aspiring settlers followed the

canal straight into the Great Lakes homelands of the Potawatomi and other

Native nations. This onslaught of white newcomers in the 1820s disrupted food

supplies and cultural practices, sparked violent encounters, and introduced

fatal diseases. Leaders such as Leopold Pokagon or Sakekwinik struggled to

contain the damage.

Then, in 1830, President

Andrew Jackson signed the Indian Removal Act. This new law sanctioned ongoing

efforts to push Native peoples west of the Mississippi. Pokagon learned that

even the Baptist missionary living in his community supported Jackson’s removal

program. In response, Pokagon cut ties with white Protestants in search of a

more favorable religious and political alliance.

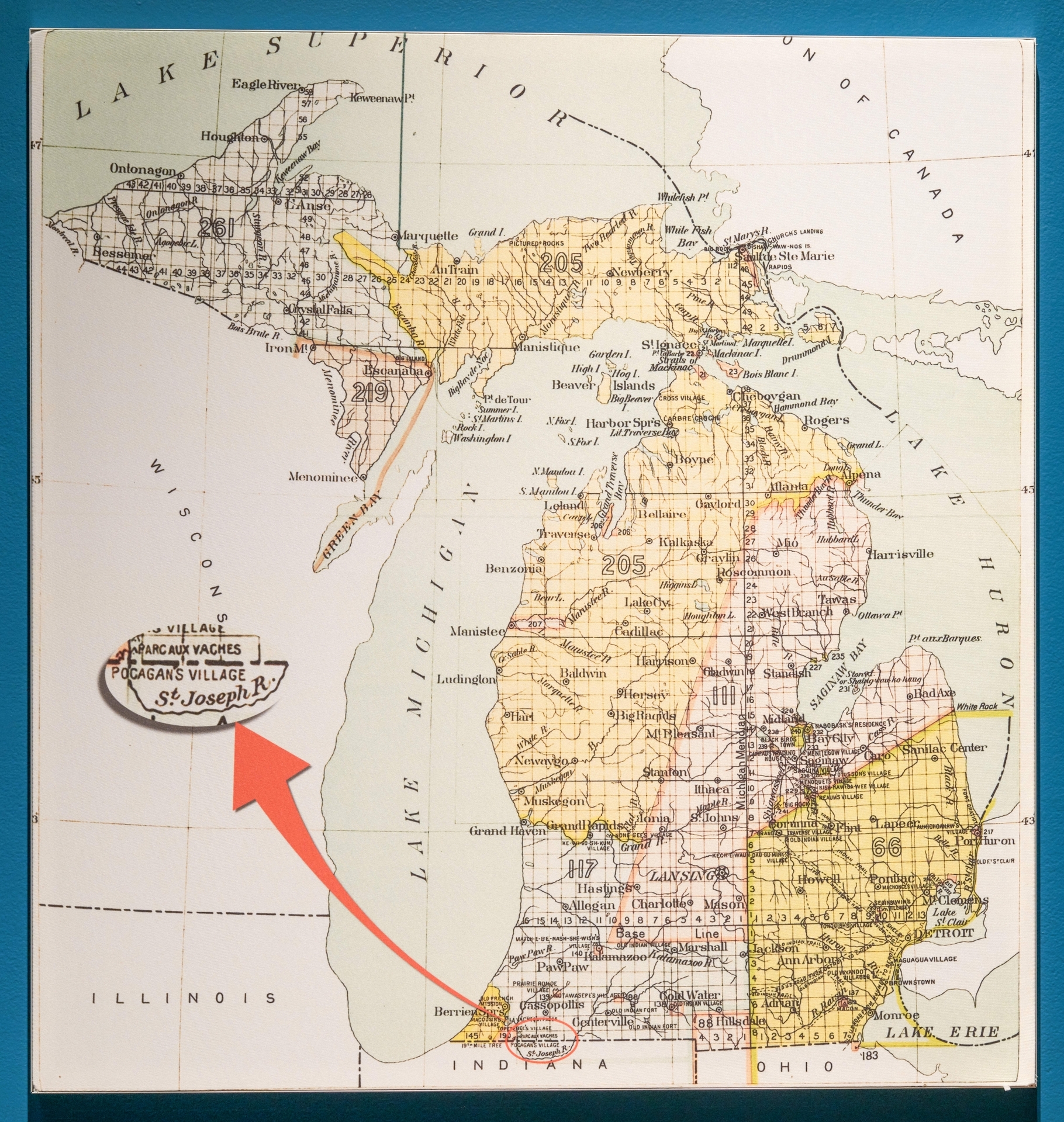

Catholic Allies

Leopold Pokagon’s band of

Potawatomi lived in the St. Joseph River Valley—marked “Pocagan’s Village” at

the bottom of this map. In 1830, Pokagon left home to journey to Detroit. His

mission? To request a "black robe" (Catholic priest) for his

community. Pokagon needed allies and hoped Catholic leaders within the new

Diocese of Cincinnati would help him oppose removal.

Pokagon’s quest was

successful. Impressed with his sincerity and eager to regain influence among a

people once welcoming to French Jesuits, diocesan leaders agreed to send Father

Stephen Badin to establish a mission at Pokagon’s village.

Badin earned Pokagon’s trust.

Many Pokagon Potawatomi—including Pokagon and his wife Elizabeth Topinabee

(Ketesse)—embraced the Catholic faith. Prayer books like this one allowed the

community to read prayers, psalms, and devotions in their own language.

Indian land cessions in the United States, Michigan

Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division

A Religious Exemption

In 1833, Leopold Pokagon

joined 6,000 other Potawatomi in Chicago to negotiate the Treaty of Chicago. US

officials wanted the Potawatomi to cede their lands and move west of the

Mississippi. Pokagon helped negotiate an amendment to the treaty. The amendment

permitted his band to remain in Michigan “on account of their religious creed.”

This map depicts Chicago in

the year of the treaty. It visualizes Native people pushed to the margins, a

future envisioned by the Indian Removal Act. Pokagon won an exemption from

removal by claiming a shared Christianity with the colonizers. But within a

handful of years, other Potawatomi were driven from their homelands. An 1838

forced march to Kansas is known as the “Trail of Death.”

Despite the confident

projections portrayed in this map, resistance from leaders like Pokagon slowed

the speed of “Indian Removal.” Pokagon's decision to ally with Catholic

missionaries who supported his goals was just one example.

Lawrence C. Earle

The Last

Council of the Pottawatomies, 1833, 1900

Chicago History Museum, ICHi-062506

Staying in Place

Pokagon suspected that

Christianity alone would not protect his people from removal. In 1836, he

bought 874 acres of land north of his original village, in what is now Silver

Creek Township, and moved there with his band. In 1840, federal troops

attempted to remove all remaining Potawatomi from the state, disregarding the

Pokagon Band’s exemption. This time, Pokagon received support from Michigan

Supreme Court justice Epaphroditus Ransom, who confirmed the band’s right to

stay largely because Pokagon’s land purchase was legally protected as private

property.

One legacy of the Pokagon

Band’s ability to stay in place is the ongoing tradition of black ash

basketmaking. Black ash trees are native to the swampy areas of the Great Lakes.

Properly harvesting the wood requires specific environmental knowledge. These

trees do not grow in the western climate where the US government sent many

Potawatomi. Pokagon Band members have helped their western relatives maintain

this important part of their culture.