Marriage

After the Civil War, Congress

again turned its attention to Utah. The attempt by anti-polygamists to deny US

citizenship to those practicing plural marriage provoked a massive “Indignation

Meeting” organized entirely by women. Over 3,000 women gathered in Salt Lake

City's great tabernacle to demand religious liberty for themselves and their

families.

When the proposed legislation

failed, federal officials turned to enforcing the law against plural marriage

passed during the Civil War. Church leaders responded by sending a test case to

the US Supreme Court. Their lawyers argued that criminalizing polygamy trampled

on the constitutional and territorial rights of Utah's Latter-day Saints. Not

so, the Justices ruled: The Constitution protected belief in polygamy, but Congress could outlaw its practice. Reynolds v. US (1879) was the first high court decision to place

limits on religious freedom.

Over the next decade,

campaigns against polygamy escalated. In Congress, new acts harshened the

penalties for plural marriage, fractured Mormon families, and dissolved the

Church’s corporate status. These punitive measures also threatened completion

of a massive temple under construction in the center of Salt Lake City.

“A

Polygamous Family,” Women of Mormonism,

1882

Patricia

D. Klingenstein Library, New-York Historical Society

Salt Lake Temple

Church History Museum, Salt Lake City

Sister Wives

These four women, all plural

wives of high Church leaders, were among the first to embrace plural marriage

in Nauvoo, Illinois. They had experienced mob violence, banishment from their

homes, the trials of the overland trail, and the indignity of being portrayed

as ignorant women in thrall to lecherous patriarchs.

All four treasured their

gathered community and valued sacred rituals. They also treasured their

identities as citizens. They used the 1870 “Indignation Meeting” not only to challenge

Congress but also to ask Utah legislators for the vote. They got it several

weeks later, joining the women of Wyoming Territory in gaining suffrage.

“Were we the stupid,

degraded, heartbroken beings that we have been represented, silence might

better become us; but, as women of God—performing sacred duties—we not only

speak because we have the right, but justice and humanity demand that we

should.”

—Eliza

Snow, 1870

Zina Huntington Young, Bathsheba Smith, Emily Partridge

Young, and Eliza Snow, 1867

Courtesy Church History Museum, The Church of Jesus Christ

of Latter-day Saints

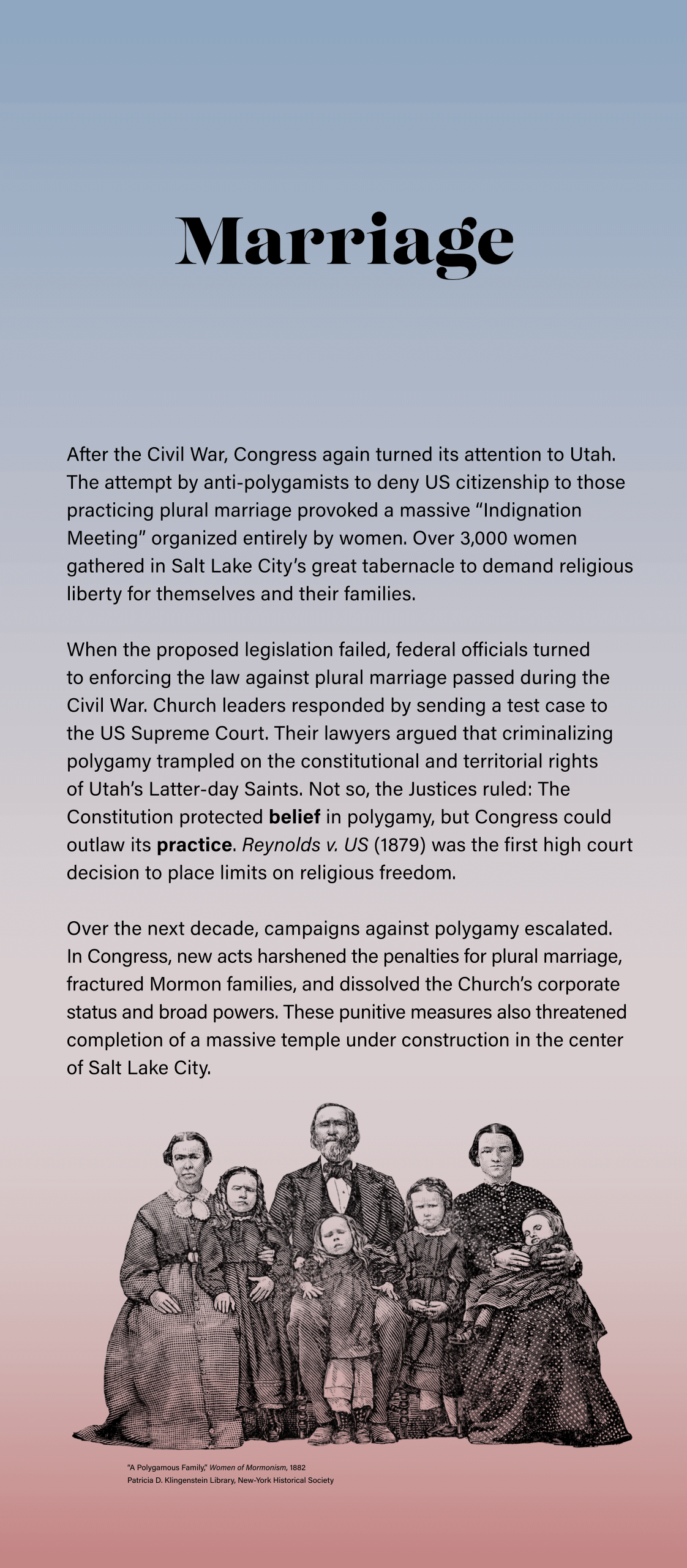

Mormon women rallied in 1879 to

defend their marriages and their religion. That same year, the Supreme Court

ruled that polygamy was not constitutionally protected.

“Detachment

of 400 Mormon Women,” Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, 1879

Patricia

D. Klingenstein Library, New-York Historical Society

Anti-Mormon political

cartoons regularly appeared in the popular press.

"The Elders’ happy home,” Chic,1881

Patricia

D. Klingenstein Library, New-York Historical Society

In Reynolds v. United States (1879) the Supreme Court first defined

limits to religious liberty.

The Waite Court, 1876

Supreme Court of the United States

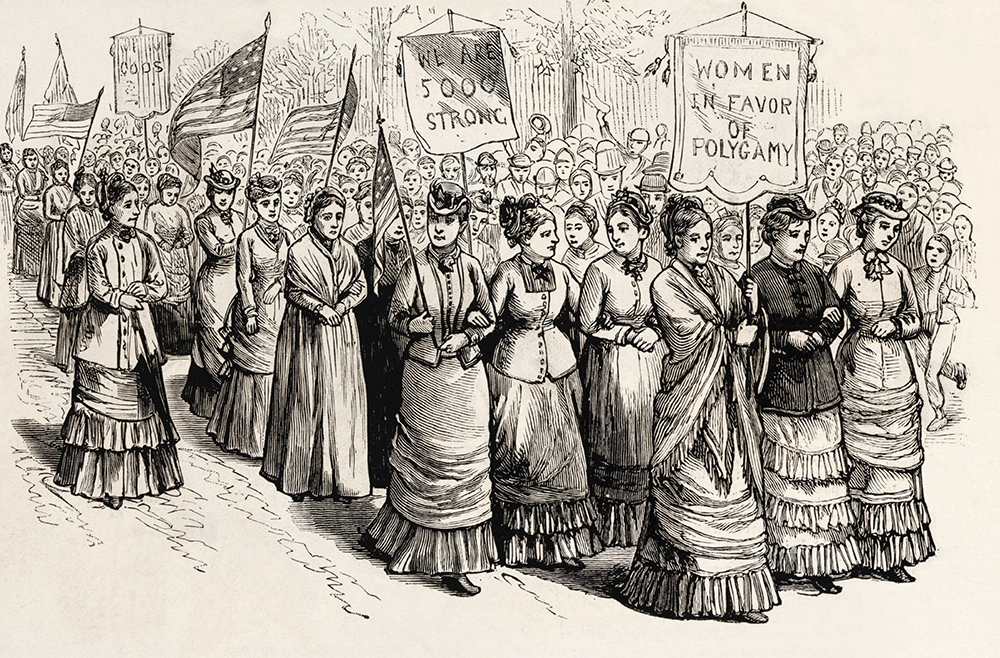

Polygamy Ends

1882: The Edmunds Act made

polygamy a felony and intensified enforcement of anti-polygamy laws. Convicted

polygamists lost their civil rights.

1887: The Edmunds–Tucker Act

lengthened jail time for polygamy, disincorporated the Church, and confiscated

its properties. It also disenfranchised all Utah women.

1890: Fearing that continued

defense of plural marriage would destroy the Church, President Wilford Woodruff

issued a Manifesto agreeing to obey the laws against polygamy.

1896: Utah’s 7th petition for

statehood was granted, provided the state constitution ban polygamy.

Polygamists in the Utah Penitentiary, 1888

Courtesy of the Church History Library, The Church

of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints