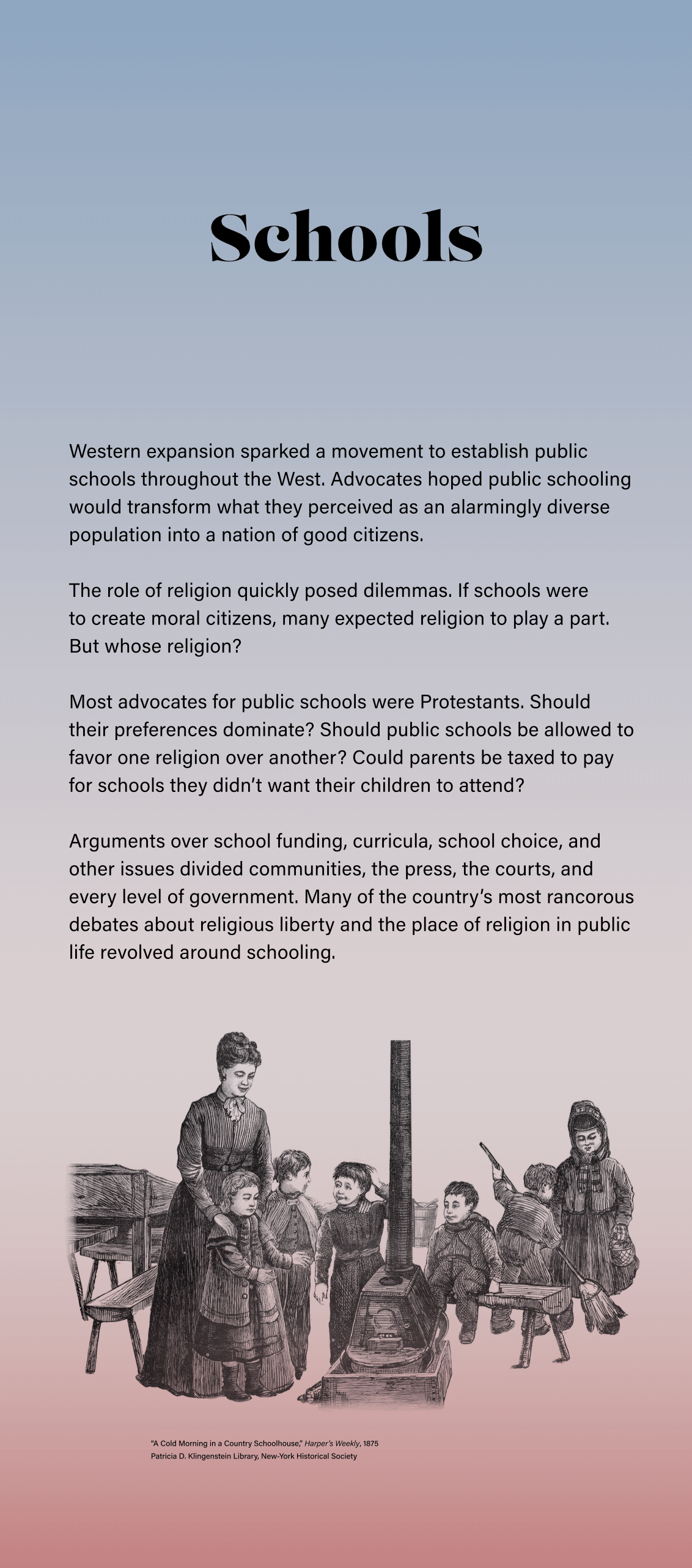

Schools

Western expansion sparked a

movement to establish public schools throughout the West. Advocates hoped

public schooling would transform what they perceived as an alarmingly diverse population

into a nation of good citizens.

The role of religion quickly

posed dilemmas. If schools were to create moral citizens, many expected

religion to play a part. But whose religion?

Most advocates for public

schools were Protestants. Should their preferences dominate? Should public

schools be allowed to favor one religion over another? Could parents be taxed

to pay for schools they didn’t want their children to attend?

Arguments over school

funding, curricula, school choice, and other issues divided communities, the

press, the courts, and every level of government. Many of the country’s most

rancorous debates about religious liberty and the place of religion in public

life revolved around schooling.

“A Cold Morning in a Country

Schoolhouse,” Harper’s Weekly, 1875

Patricia D. Klingenstein Library, New-York Historical

Society

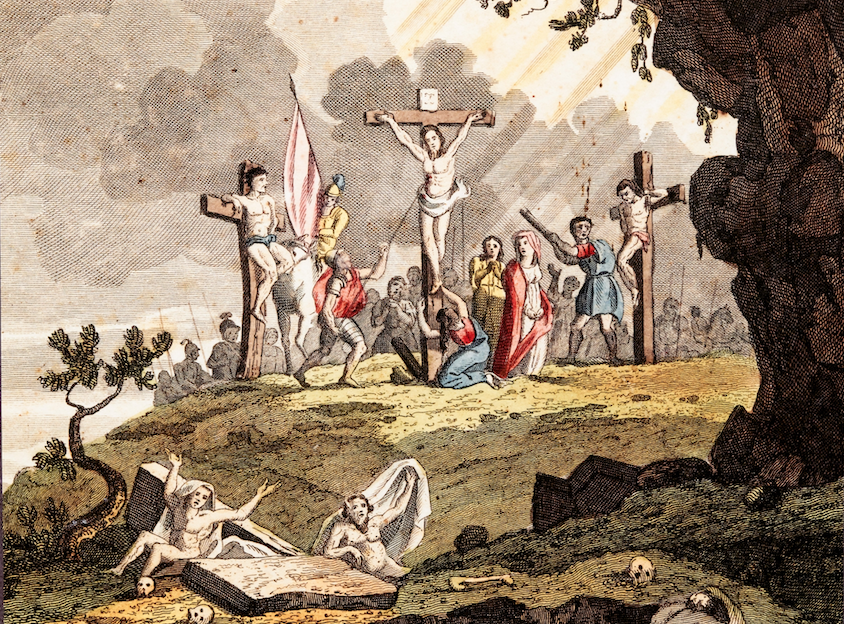

Civics

Separation of Church and State

Ten years after the Civil

War, President Grant spoke to veterans he once commanded in the Union’s Army of

the Tennessee. Of what did he speak? Religion in the schools! Grant told his

listeners that the future of their nation depended on public education free of

religious bias.

“Afford

to every child growing up in the land the opportunity of a good common school

education, unmixed with sectarian, pagan or atheistical tenets. Leave the

matter of religion to the family circle, the church, and the private school

supported entirely by private contribution. Keep the church and state forever

separate.”

Grant sought to spur a

nationwide system of public schools. He wanted to keep the schools

non-sectarian—unaffiliated with a particular religion or theology—because Protestant

voters worried about the spread of Catholic and Mormon teachings in the West.

The President’s critics countered that, in practice, his “non-sectarian”

schools were biased toward Protestantism.

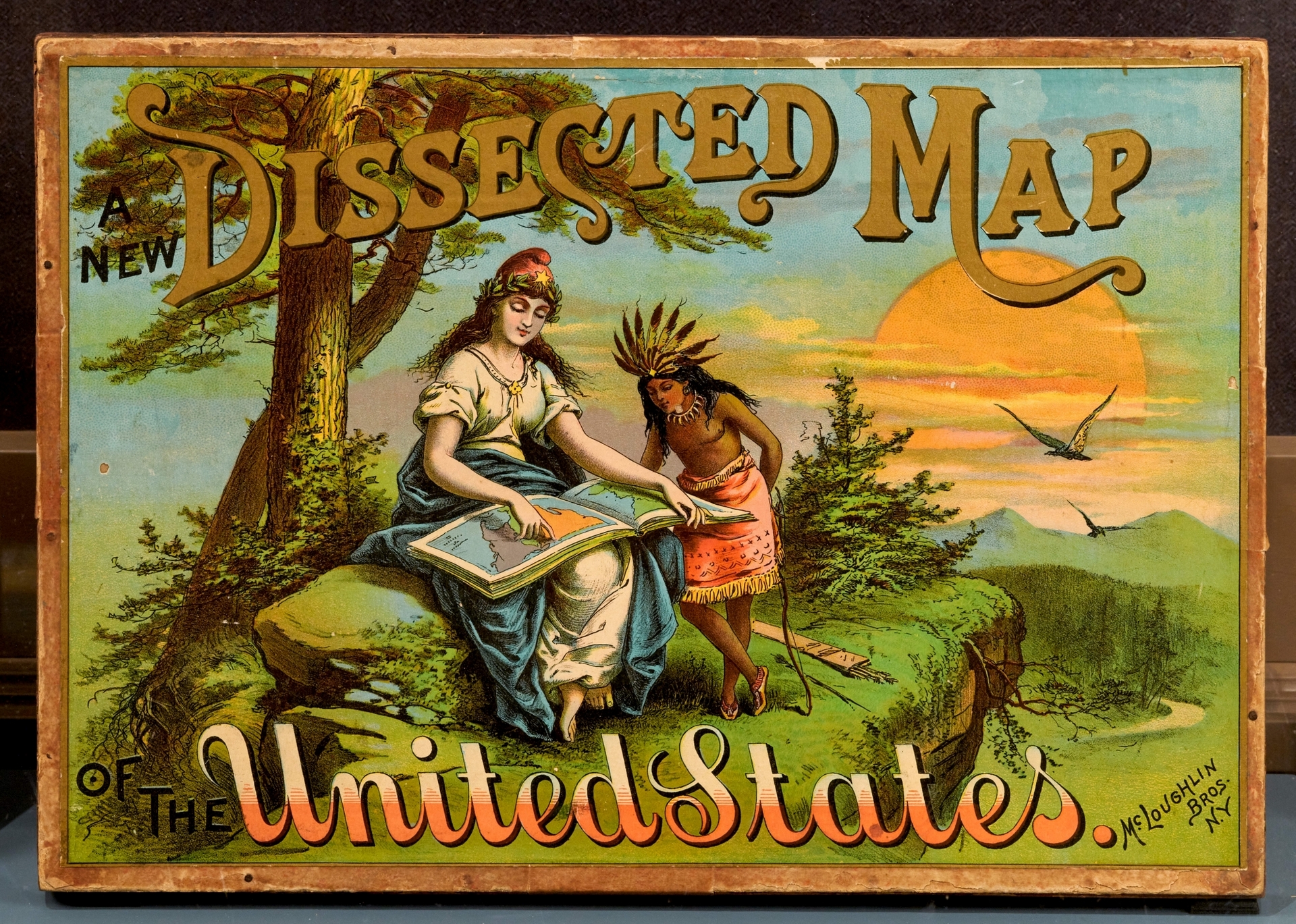

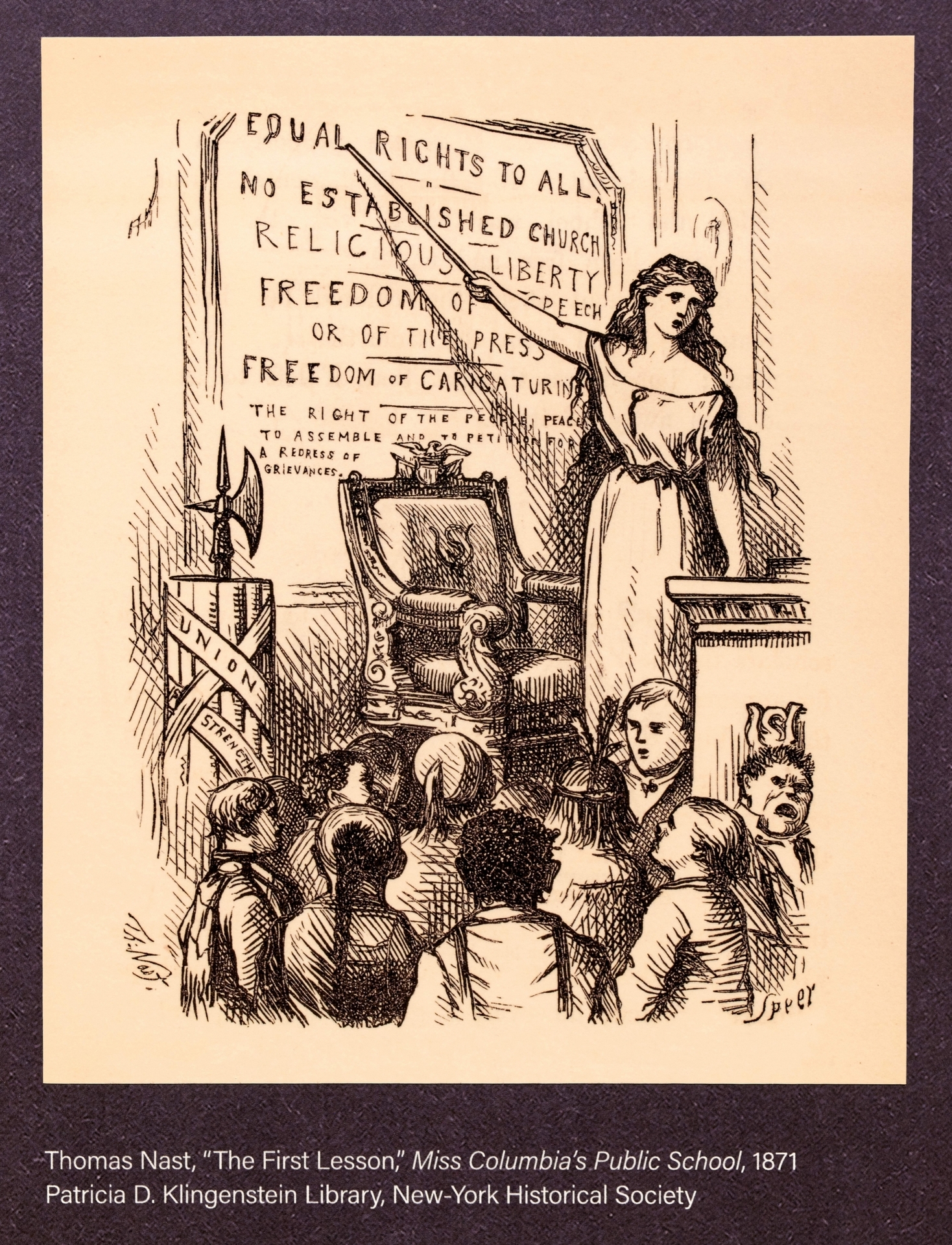

Geography Lessons

“Dissected maps” were early

forms of jigsaw puzzles designed to make learning fun. This one is a map of the

United States in 1887, a dozen years after the president's Des Moines speech.

The nation's political geography was still in formation, but the image on this

puzzle cover conveys confidence in the outcome.

The female “teacher”

represents Columbia—the personification of American liberty—who tutors an

Indigenous pupil. At the time, Americans would have understood the image as a

metaphor for civilizing and Christianizing the continent.

McLoughlin Brothers

A New

Dissected Map of the United States, ca. 1887

New-York Historical Society, The Liman Collection,

2000.547

Arithmetic

School Funding

With the Northwest Ordinance (1787), the

Continental Congress created a

system for opening schools west of the Appalachian Mountains. Land recently

taken from Native nations was divided into townships with plots sold to white

settlers. A portion of each township was dedicated to supporting new schools.

Public lands and funds

continued to support western schools as the nation grew. Instruction in these

classrooms often reflected a Protestant bent, even while the responsible

parties imagined them as religiously neutral, or non-sectarian. These school

leaders thus believed the lessons were suitable for a religiously diverse

student body.

One school superintendent expressed

this point of view in his clearly Protestant book of lessons. “There is no

better place to teach reverence for the God of heaven than the school-room,” he

wrote. “It can be done without inculcating sectarian dogmas or trampling upon

the rights of conscience.”

Non-Protestants, particularly

Catholics, sought to change this status quo. They argued for their own portions

of the school fund and against paying taxes for schools whose teachings they

disagreed with.

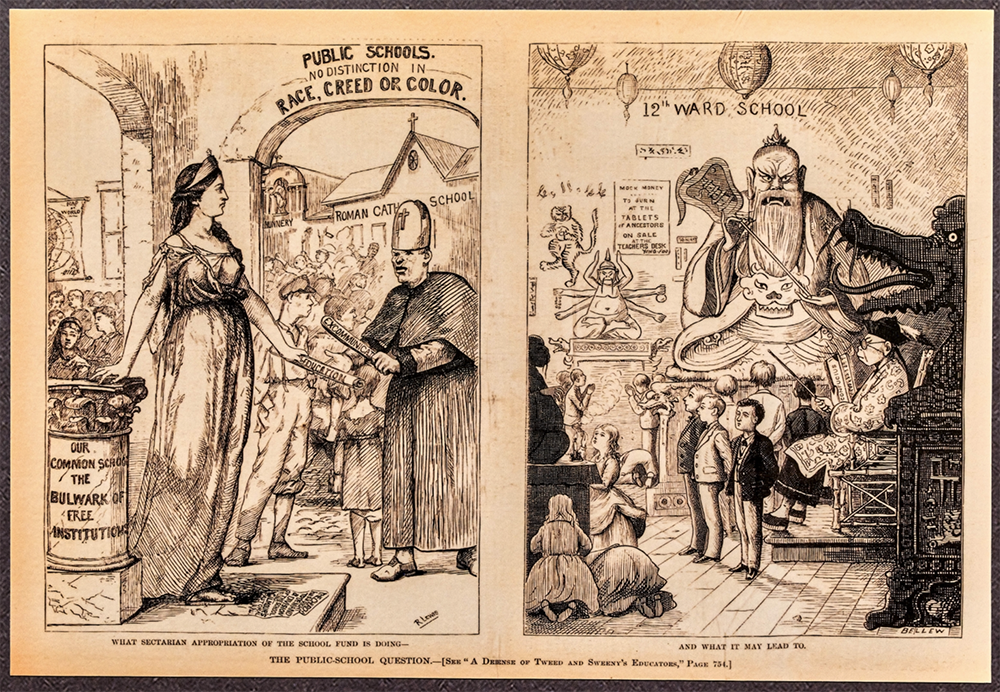

"What Sectarian Appropriation is Doing … And What It

May Lead To,” Harper’s Weekly, 1873

Patricia D. Klingenstein Library, New-York

Historical Society

Pressing Debate

With this biting political

commentary, Harper’s Weekly newspaper

dove into the strident debate over public funding for sectarian schools (whose

religious teachings privilege a specific group or theology).

The cartoon argues against

giving Catholics a portion of school funds for the operation of separate

religious schools. It warns that in addition to threatening American freedom,

such funding would set a dangerous precedent by

someday subsidizing other religious schools the public might find even more

objectionable.

Moral Improvement

Teaching Morality

America’s divergent religious

groups shared the belief that their own religion nurtured morality. Many thus

reasoned that religion belonged in the classroom. Nebraskans explicitly connected

religion, morality, and schools in their 1875 state constitution:

“Religion, morality, and

knowledge being essential to good government, the Legislature shall pass

suitable laws to protect every religious denomination in the peaceable

enjoyment of its own mode of public worship, and to encourage schools and the

means of instruction.”

But in the exceptionally

diverse nation that western expansion helped create, whose moral teachings

would get priority? Who would decide whose teachings dominated? And if all

religion was removed from the classroom, could children still be taught to

distinguish right from wrong? Debate raged over these and other questions.

Lord’s Prayer Controversy

This handkerchief, with its

mix of moral and religious messages, may have been created for use in a

Protestant Sunday school. Though many Americans believed that moral instruction

rooted in Christianity should also be included in public schools, doing so in a

religiously heterogeneous society presented difficulties. In many places it led

to ongoing skirmishes.

The

Lord’s Prayer aroused particular animosity in San Francisco, whose schools

served Protestant, Catholic, and Jewish children. The Protestant version of the prayer had

once been mandated in city schools. Over the years, its declining use aroused

both cheers and bitter denouncements. In 1875, the Lord's

Prayer was banished as a sectarian violation of school regulations.

Sunday Lessons No. 1, 1850–55

New-York Historical Society, Purchased from Elie

Nadelman, 1937.604

Industrial Arts

Christian Citizens

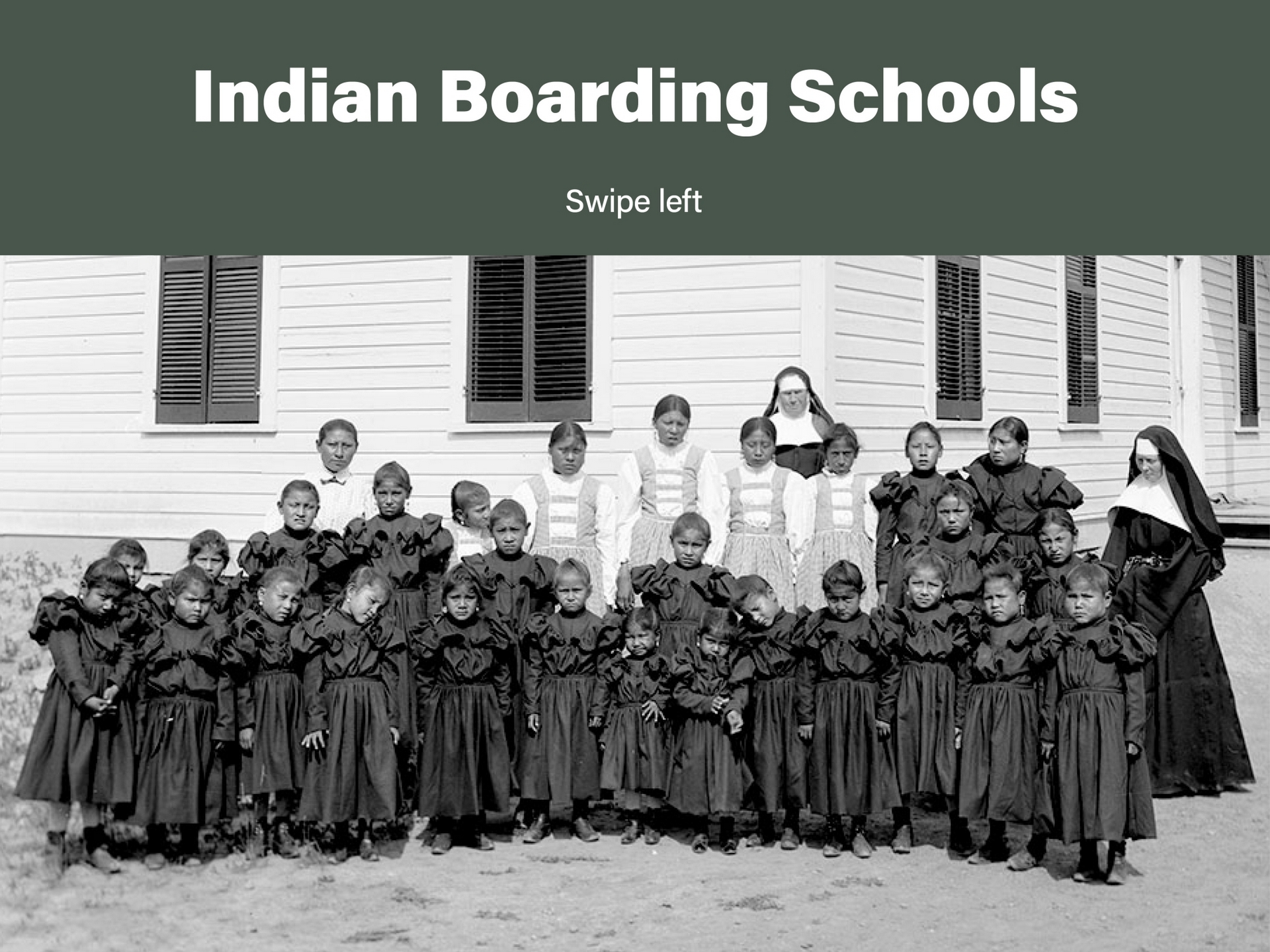

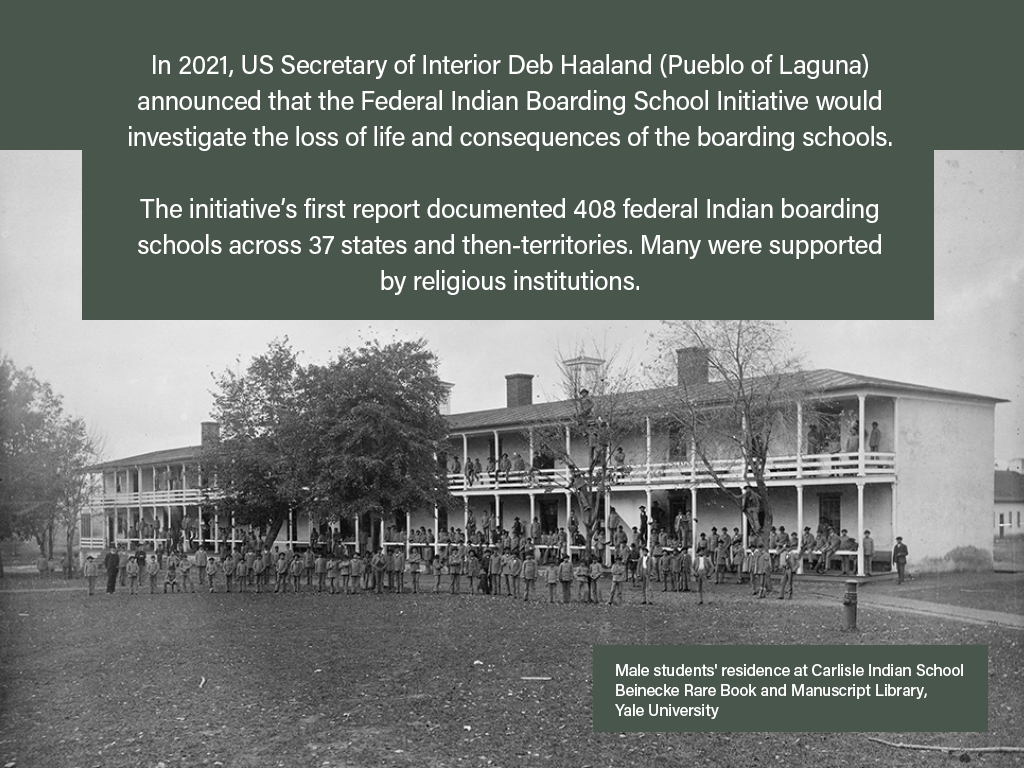

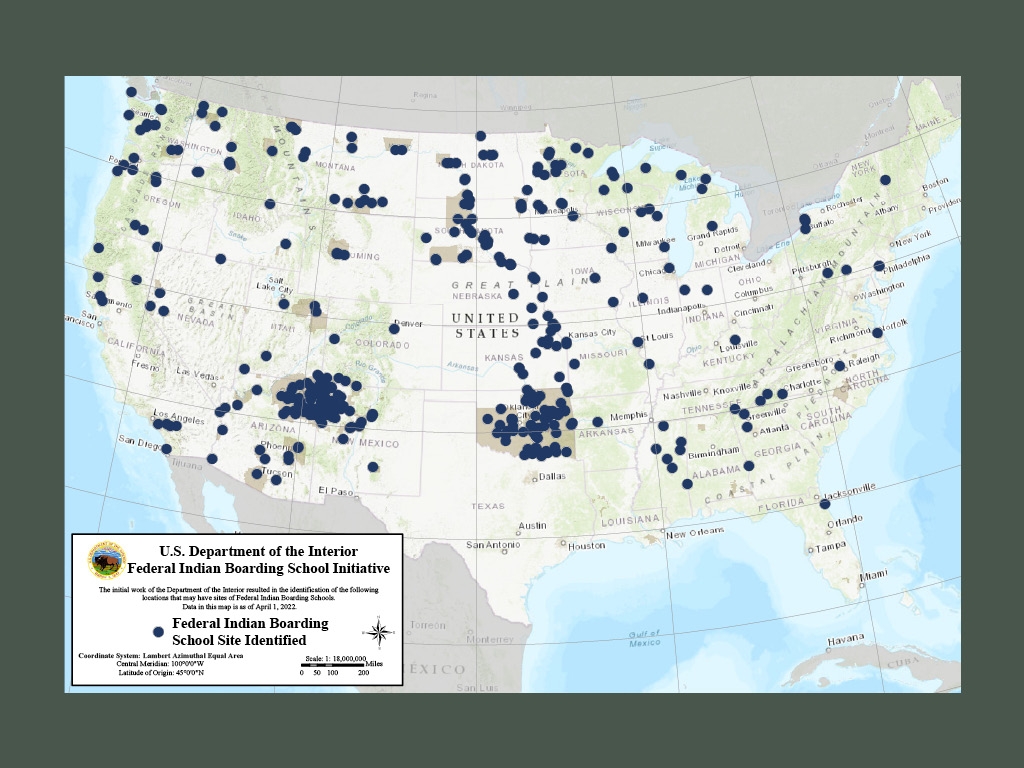

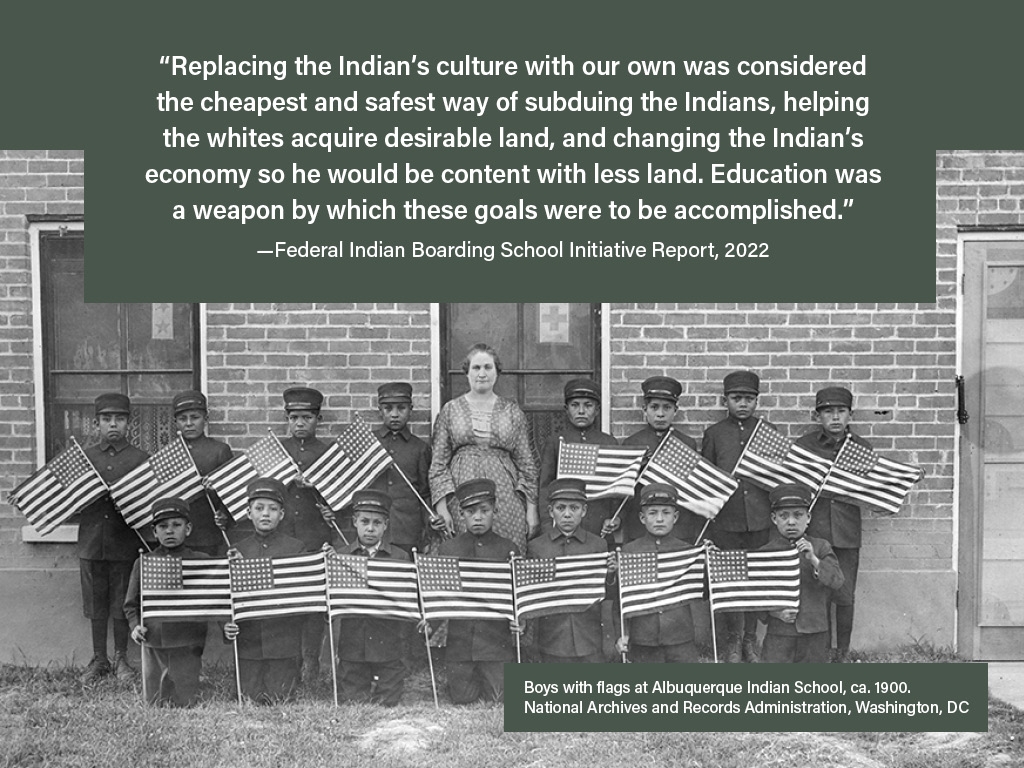

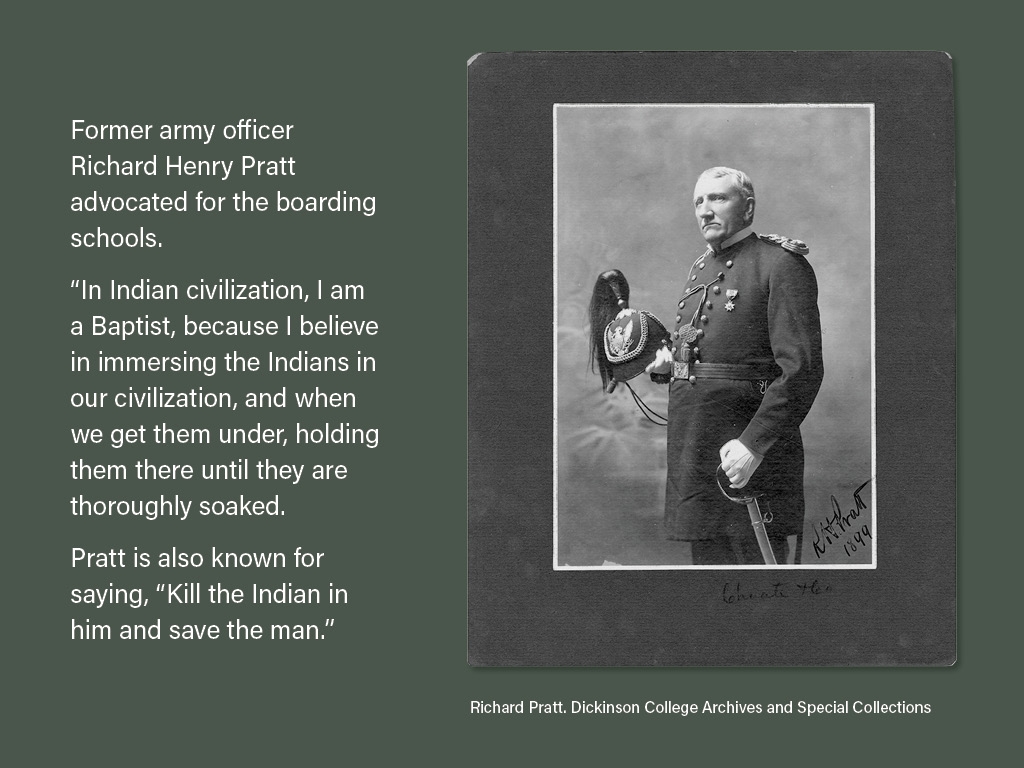

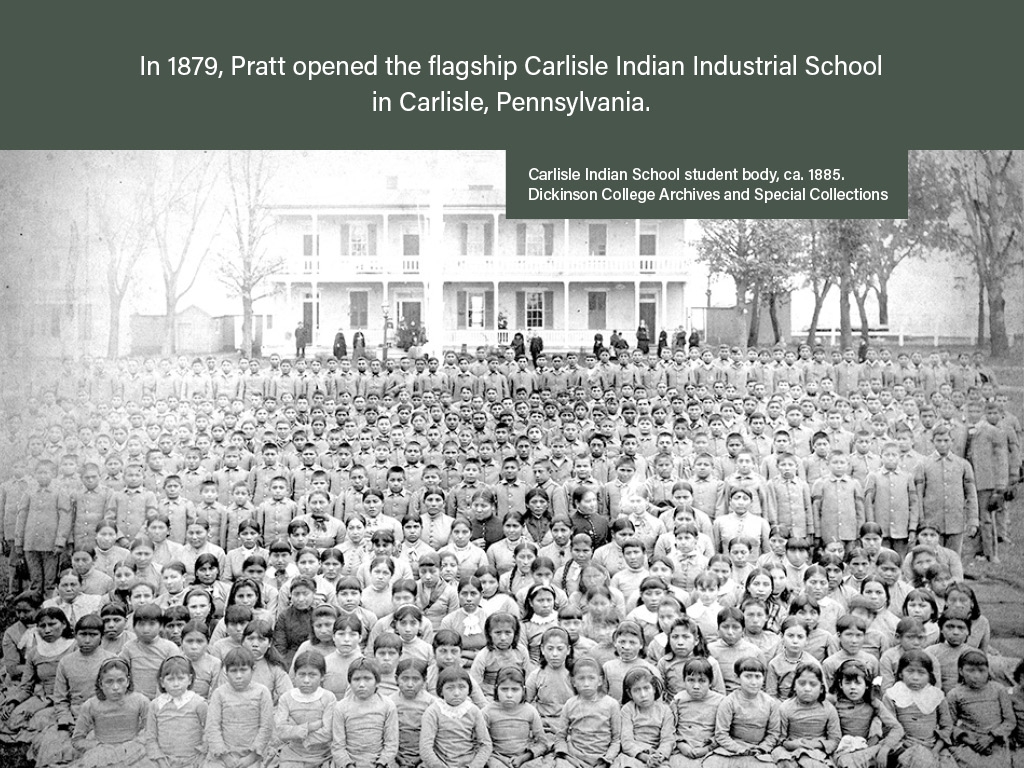

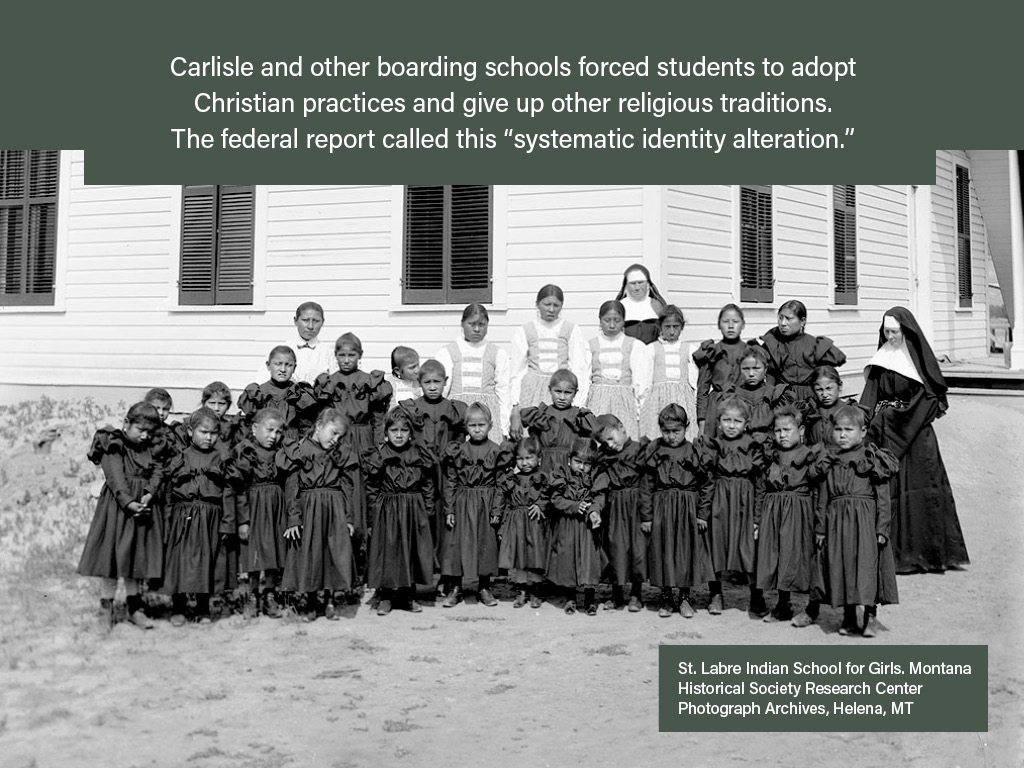

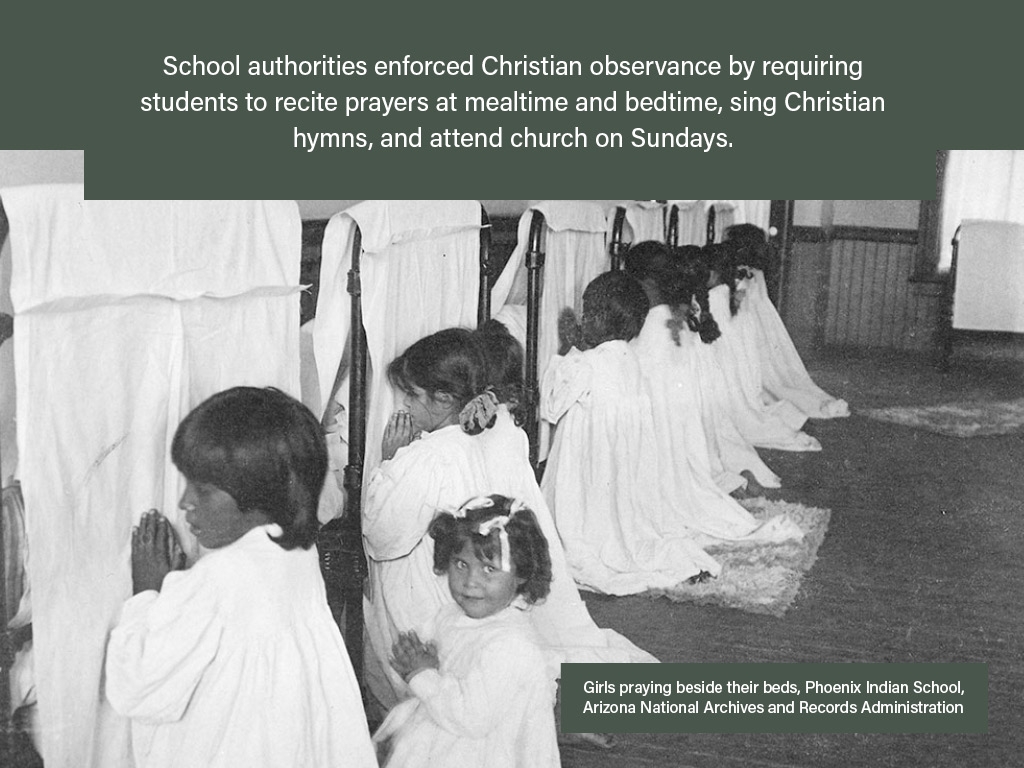

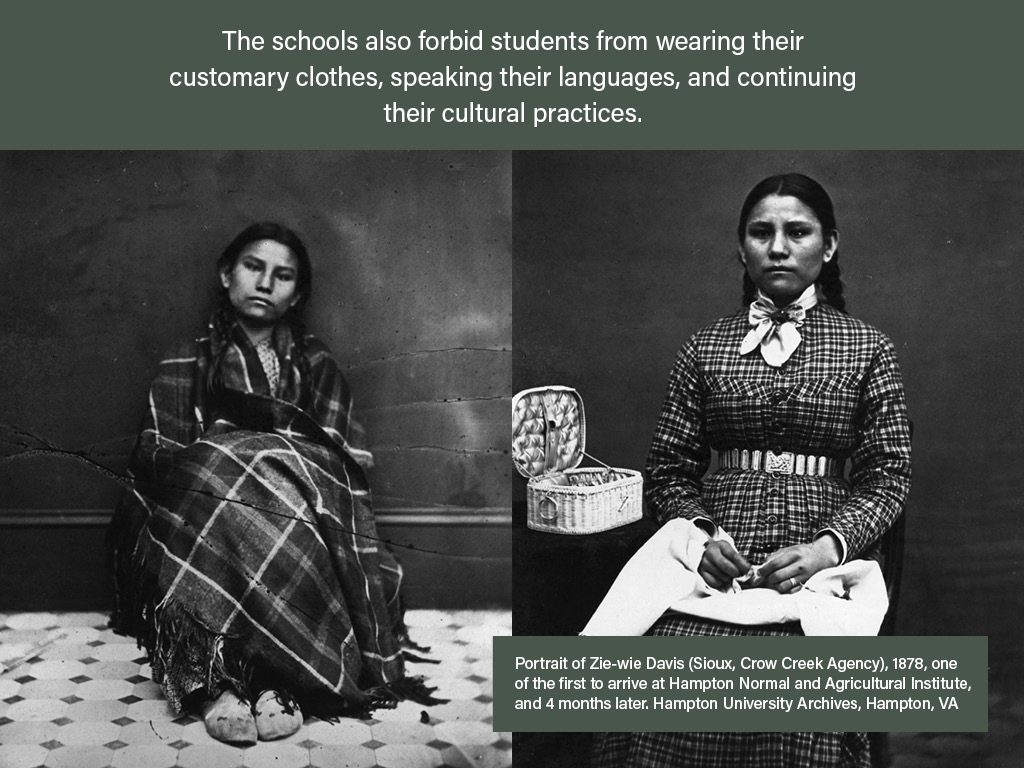

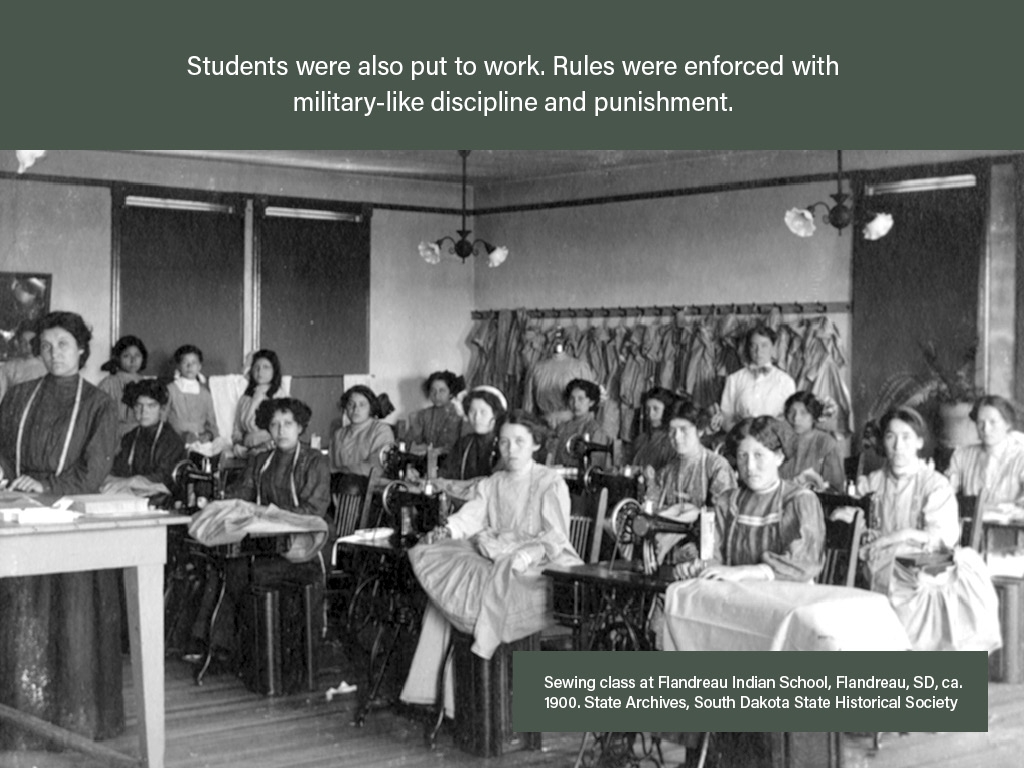

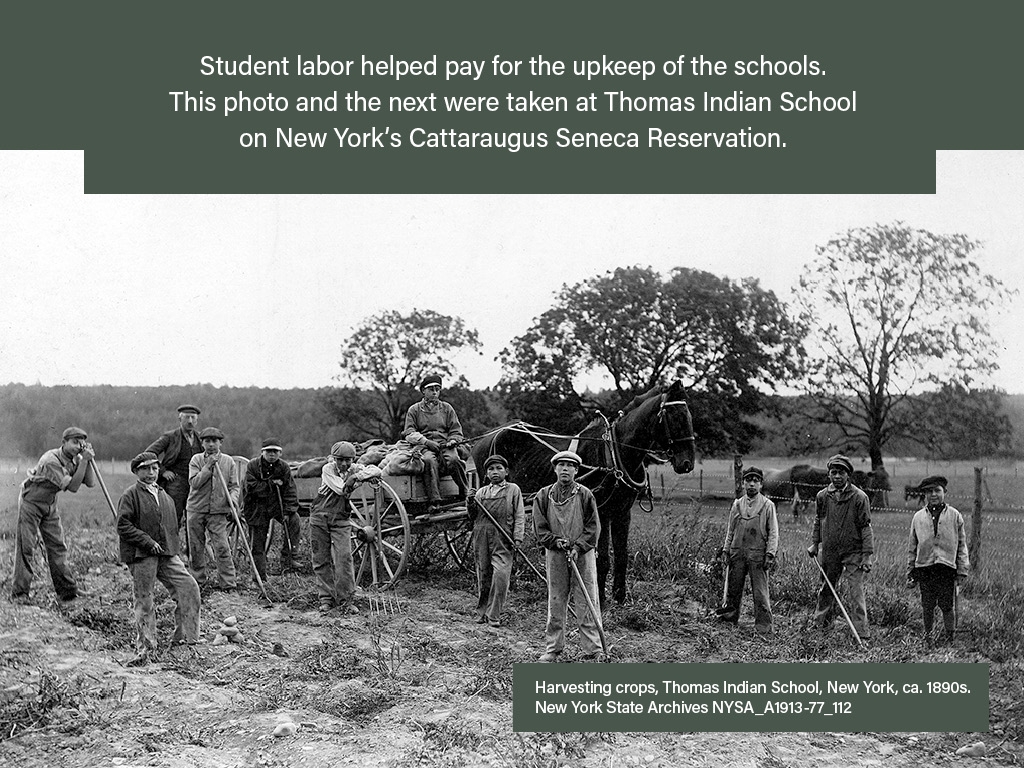

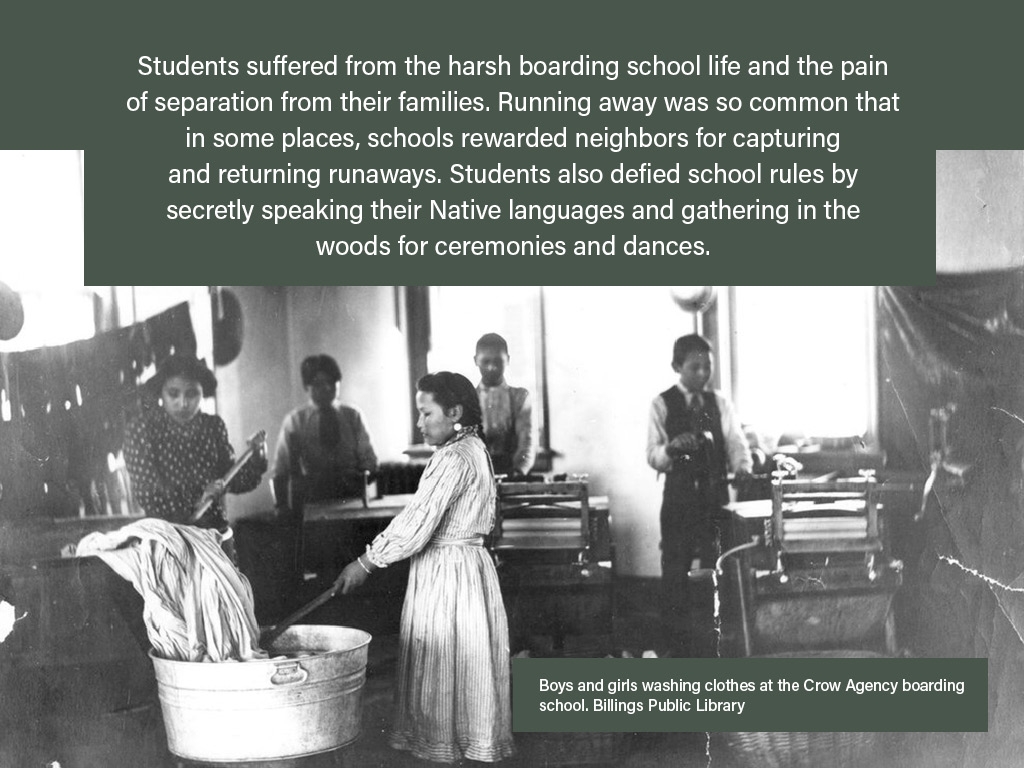

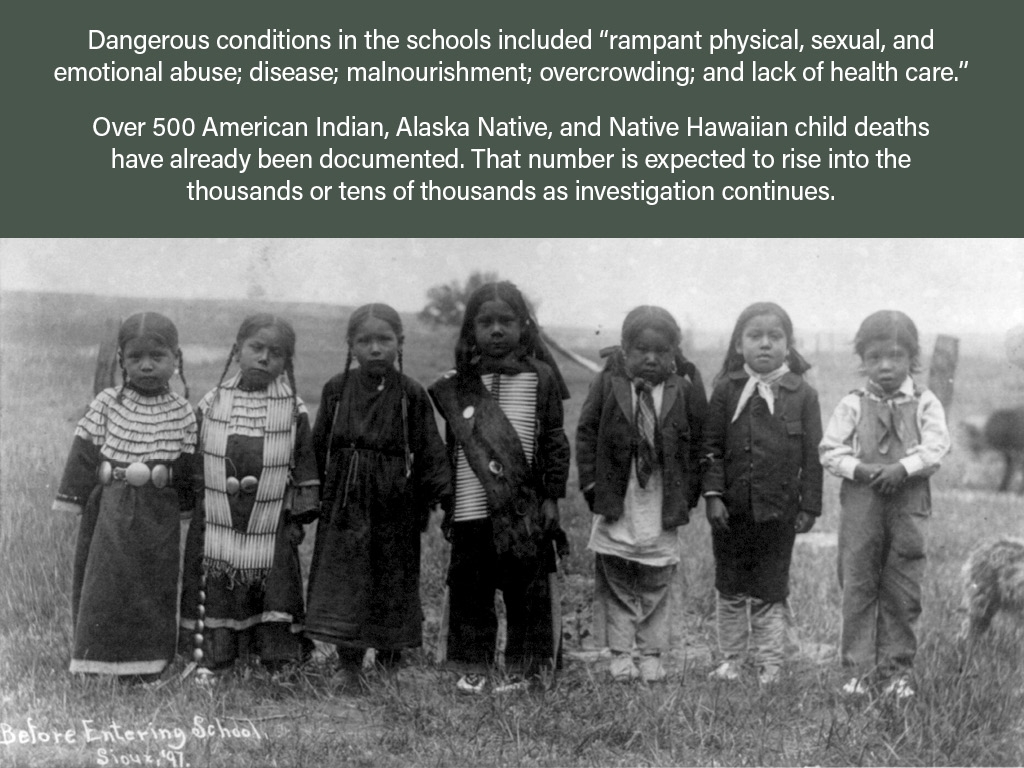

Indian boarding schools

explicitly aimed to Christianize Native children. Some institutions, like the

Ramona School for Indian Girls, were founded by Christian organizations under

contract with the US government. Others were run directly by the government as

Christian enterprises.

Few non-Native people

considered Indigenous beliefs to be religions or worried about the US

government imposing Christianity on Native children.

With most Native peoples now

forced onto reservations, government agents could compel or coerce families to

part with their children for years. Parental consent was not required.

Boarding school experiences

varied, but conditions were often harsh and could be deadly. Instruction in

Christianity, industrial training, and labor did the “civilizing work” that

supporters believed would assimilate Native children into white society.

Native families went to great

lengths to stay connected to children attending boarding schools. This photo

documents Cheyenne parents camping near the Cantonment Boarding School in

defiance of government aims to separate the children from their communities.

Tipis

in field at Cantonment Oklahoma Indian Boarding School, 1899–1900

Denver

Museum of Nature & Science, BR61-369

“In Eastern towns, it is hard

for educators to induce parents to walk a distance of two or three blocks to

visit their children in school. The Apache Indian will ride on horseback one

hundred and eighty miles, two or three times during the school term, to see how

his children are progressing; while the Pueblo will walk thirty or forty miles

for the same purpose.”

—Excerpt

from Ramona School for Indian Girls, 1886

These before and after photos

advertised the Ramona School’s work to “civilize” Native children entrusted to

its care.

Such images helped schools like Ramona solicit funds and support.

Apache Girls on Arrival at the Ramona School, Santa

Fe, N.M.” and “Apache Girls Six Days after Arrival at the Ramona School,” in The Ramona School for Indian Girls: Santa

Fe, N.M., 1886

Patricia D. Klingenstein Library, New-York

Historical Society

Religion

School Choice

Catholic Church officials and

parents wearied of their struggles over religion in the schools. They had

fought to make public school curricula more welcoming to Catholics. They had

campaigned for a share of public funds to operate Catholic schools. Yet despite

their growing numbers, these aims remained largely out of reach.

In 1875, the Church took a

firm stance against the public schools. The Vatican declared that sending

American Catholic children to public schools would result in "evils of the

gravest kind." US Catholic bishops were directed to “spare no pains” in

improving and increasing the number of Catholic schools. They were to impress

upon the faithful the importance of enrolling their children and the necessity

of paying tuition (in addition to public school taxes).

The eventual growth of a

separate parochial school system depended largely on the labor of religious

sisters. By 1900, more than 40,000 nuns worked in parish schools.

“Jesus Crucified” lesson board

Patricia D. Klingenstein Library, New-York

Historical Society

Reading

Religious Liberty

In religiously diverse Cincinnati,

Ohio, city leaders considered their schools to be non-sectarian because they

assigned readings in the King James Bible without accompanying instruction.

Competing Protestant denominations were satisfied but not Catholics, who

preferred the Douay-Rheims Bible and

believed that biblical interpretation should be guided by the Church.

Jews and free-thinkers preferred no Bible

reading at all in school.

In 1869, Cincinnati’s school

board voted to stop all classroom Bible reading as a way to appease dissenting

parties. Some parents were relieved because their children would no longer be

instructed in religions or theologies not practiced at home. Others criticized

the compromise, arguing that it entirely removed religion from school.

A group of Protestant parents

sued to have Bible readings reinstated. They won in Cincinnati’s civil court.

The school board appealed. Ohio’s Supreme Court unanimously ruled for the

school board and reinstated the ban.

The justices determined that

Bible reading was a religious exercise and inconsistent with state constitutional

principles, even when conducted without comment and for the purpose of

instilling morality rather than religious devotion.

“Let

the state not only keep its own hands off religion, but let it also see to it

that religious sects keep their hands off each other.”

—Minor v. Board of Education (1873)

The court’s decision in the "Cincinnati

Bible War" was an important 19th-century step toward religious neutrality

in public education. But Bible

reading remained widespread in public schools well into the 20th century.

Doctrinal Differences

The King James Bible and the Douay-Rheims

Bible are two different versions of English language Christian Bibles from the

17th century. Protestants have historically favored the King James Version;

Catholics, the Douay-Rheims.

Unlike the Jewish Torah seen

earlier, both versions include the

New Testament, which Judaism does not recognize as a foundational text.