Railroad Workers

The transcontinental railroad,

completed in 1869, linked the eastern seaboard to the Pacific Ocean.

The

Central Pacific Railroad Company recruited roughly 15,000 Chinese laborers to

build the railroad’s western leg.

Crossing Mountains

To build the transcontinental

railroad across the Sierra Nevada Mountains, the largely Chinese workforce set

explosives, bore tunnels, and labored at precarious heights. Over 1,000 workers

died while performing these dangerous tasks.

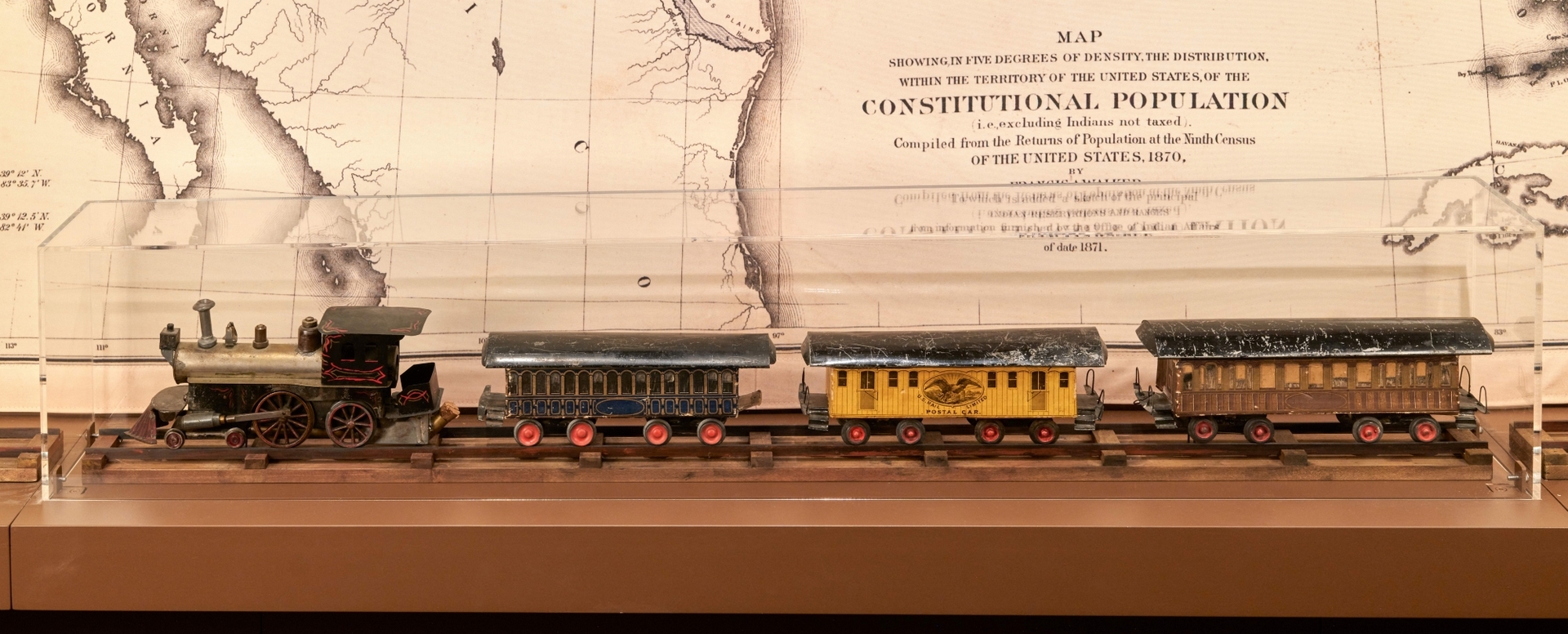

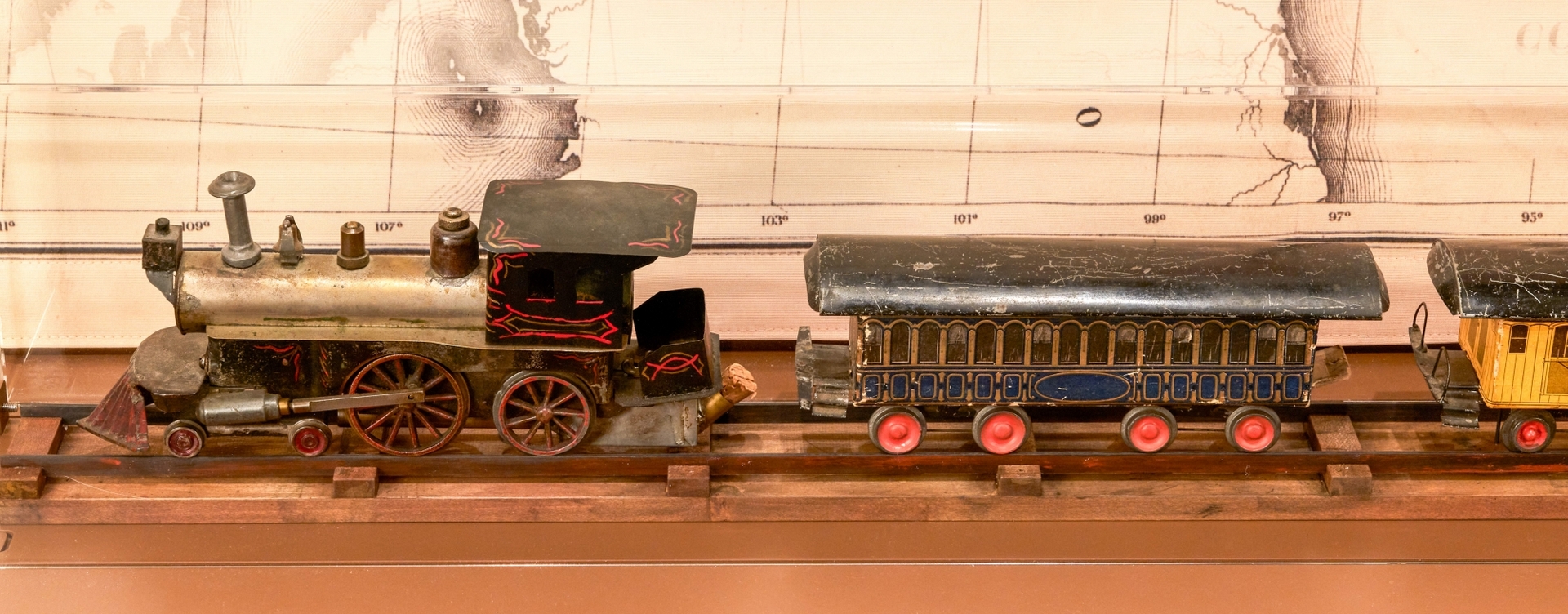

Beggs

Locomotive and train cars, late 19th century

New-York Historical Society, The Jerni Collection

Representing the US in Art

After the Civil War, Congress

funded multiple scientific surveys of western lands. Each survey generated

reams of data pertinent to the nation's economic development. But it was the

artistic products—created by photographers and artists who accompanied the

expeditions—that publicized the West for a national audience.

While surveying Colorado in

1873, photographer William Henry Jackson captured the first documentary image

of this 14,000-foot mountain in the Rockies. Its distinctive cross-shaped

snowfield had been spoken of as a Christian symbol since the time of Spanish

exploration, but few had seen it. Jackson's photograph made the Mountain of the

Holy Cross a familiar icon.

Jackson’s photograph also inspired

the western landscape painter Thomas Moran to travel to Colorado to create his

own version of this natural wonder. Moran's monumental painting went on display

in Washington, DC, in 1875, where it would have reinforced the prevailing idea

of a divinely sanctioned westward expansion.