Latter-day Saints in Deseret

The first companies of

Latter-day Saints reached the Salt Lake Valley in 1847. They called their new

home Deseret, a name Brigham Young had plucked from the Book of Mormon.

Divine guidance and knowledgeable informants had led them

here. But how could they secure it for themselves? Ute, Paiute, Shoshone, and

Bannock peoples had long belonged to this land. The United States claimed it

too. By parrying demands from all sides—sometimes with diplomacy; other times

with violence—the community put down roots.

Although Congress rejected

the Saints' bid to make Deseret a state, their vision for a godly society lived

on in Utah Territory. President Millard Fillmore appointed Brigham Young as Utah’s

territorial governor in 1850. After the Saints announced their practice of

polygamy, or plural marriage, Young lost the governorship. But he did not lose

his influence with those who considered him a prophet.

The Saints continued to

defend their church-run society and their right to religious liberty despite US

government claims that their political and religious practices made them

unworthy of statehood.

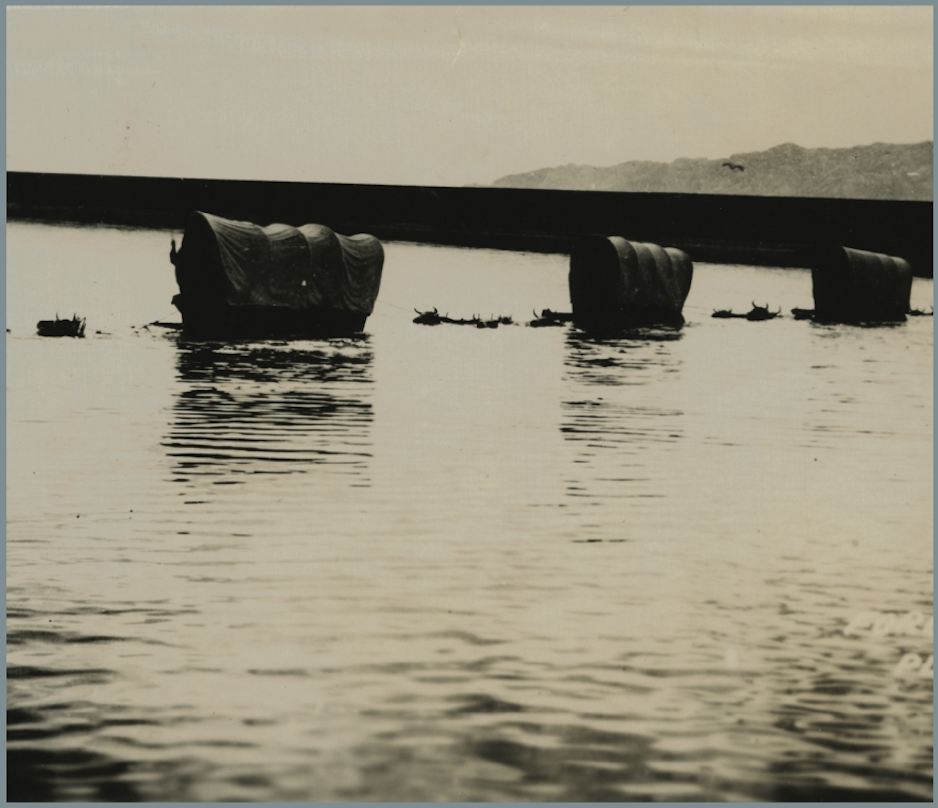

“Mormon

Convert Encampment,” Cassell’s History of

the United States, 1874–77

Patricia

D. Klingenstein Library, New-York Historical Society

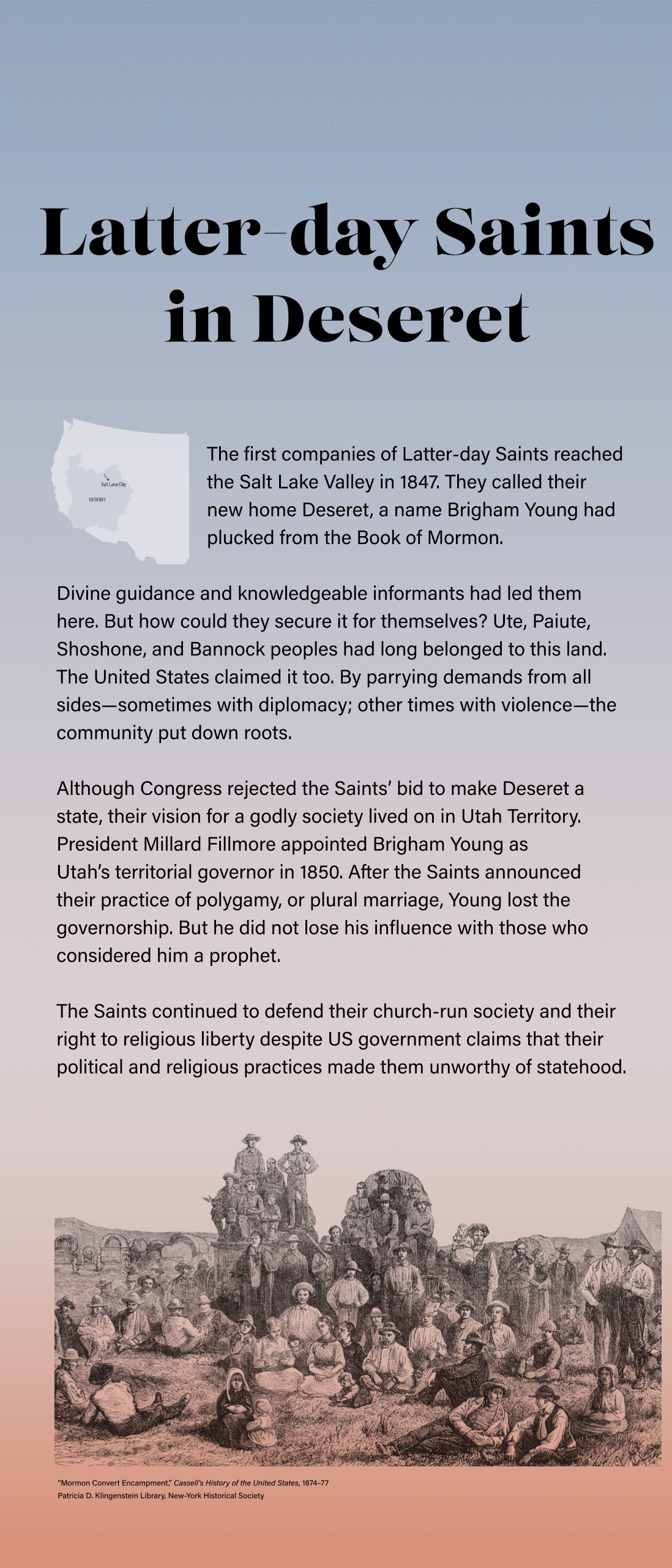

Beehive, ca. 1870

Church History Museum

Deseret & Beehives

In the Book of Mormon, the

word Deseret signified honeybee. Although most Americans understood

hives of bees as symbols of cooperative labor, in Utah that symbolism acquired

a deeper meaning. In 1854, Brigham Young installed a symbolic beehive on the

cupola of his house. The Saints believed their cooperative efforts would

fulfill the prophecy of Isaiah that the desert would “blossom as the rose.”

Successfully negotiating

with, and converting, local Indigenous groups figured high among Young’s aims.

The Book of Mormon identified

Indians as Lamanites—descendants of ancient Israelites who traveled to the

Americas before the Biblical destruction of Jerusalem. Converting Native people

would do more than secure peace in Deseret. It would fulfill Book of Mormon

prophecies.

Wakara & Brigham Young

The world of the Timpanogos

Ute leader Wakara (ca. 1808–1855) reflected the legacy of cultural disruption,

disease, and violence that began with Spanish colonization of the Southwest

several centuries before. Wakara excelled at navigating this changed

environment, achieving success as a horse trader and raider along the route to

California.

Wakara recognized both threat

and opportunity in the Latter-day Saints’ colonization. He directed Brigham

Young to settlement sites that enhanced his Timpanogos Band’s position. And he

used his trading and raiding to maintain his community's stature while coping

with the transformation of land and economy wrought by the Mormons.

In 1850, Wakara and some of

his men agreed to Mormon baptism, and Wakara received ordination as an Elder.

This position may have helped him protect Ute land and sovereignty from Mormon

expansion. But soon, with settler violence increasing and Ute subsistence at

risk, Wakara led attacks against Mormon settlements. The resulting conflicts

ended with a shaky détente in 1854.

Brigham Young, ca. 1855

L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee

Library, Brigham Young University

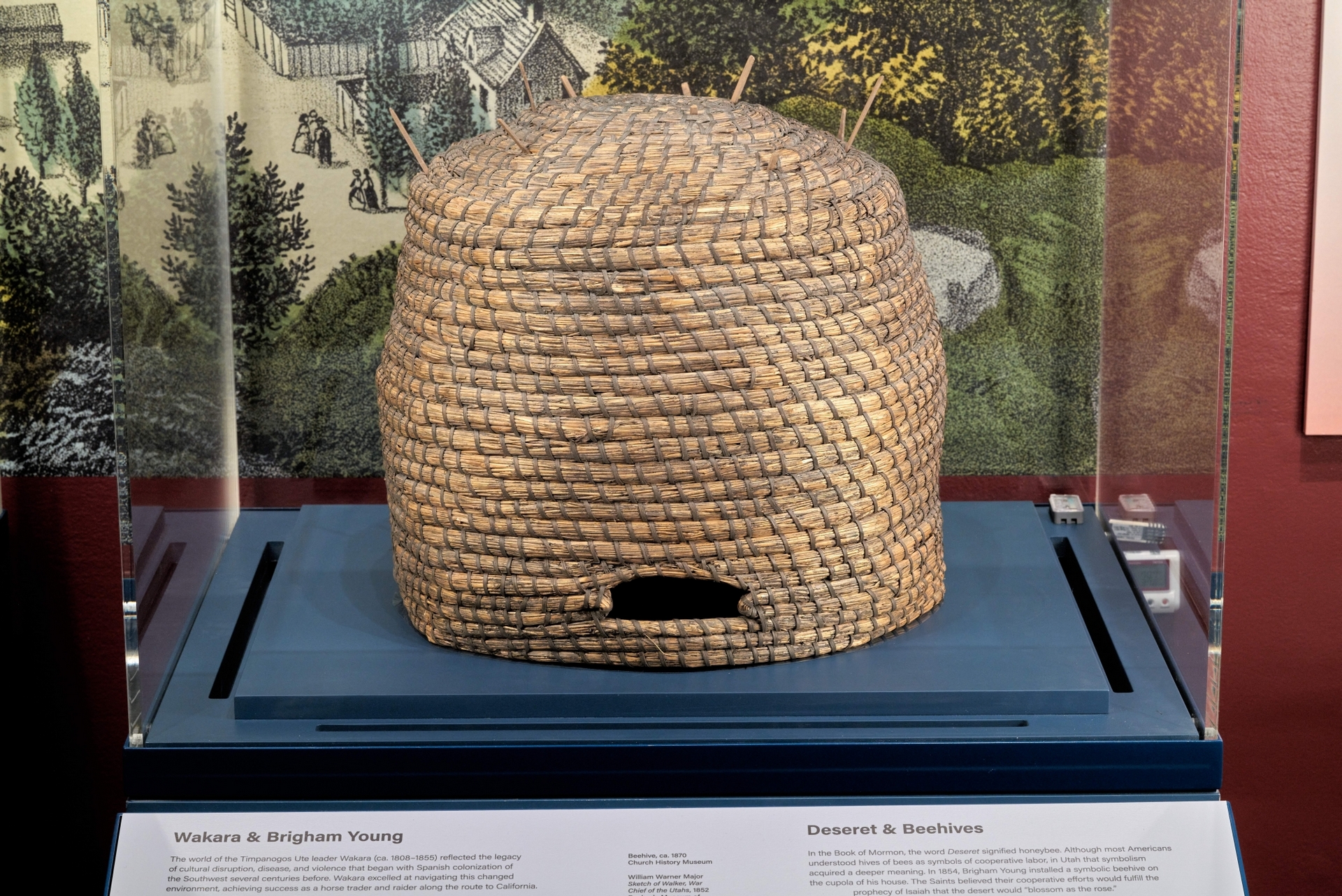

Converts & Emigrants

This trunk bears the name of a

Swiss family of converts whose members first immigrated to Utah in 1860. Such

trunks carried household goods and clothing, and might also serve as the

emigrants' first furniture once settled in their new home.

Gathering

converts from throughout the world was central to the cause of Zion. Once

baptized, the Church helped new members join their fellow Saints in Utah.

Between 1847 and the coming of the railroad, roughly 70,000 people followed the Mormon Trail to Salt Lake City.

Most traveled in Church-managed

wagon companies. Others pushed their own possessions in handcarts. A “Perpetual

Emigration Fund” supported those without resources, asking them to support

future migrants by paying back loans when they could.

Newcomers were folded into

the community through marriages and religious rituals. They also learned about

the community's trials and triumphs in church, where stories of persecution and

martyrdom were told and retold.

Wagon train crossing the Platte River, ca. 1840s–50s

Special Collections, J. Willard Marriott Library,

University of Utah

P0120 Philip T. Blair Photograph Collection

Emigrant trunk, ca. 1880

Courtesy of the Utah Historical Society

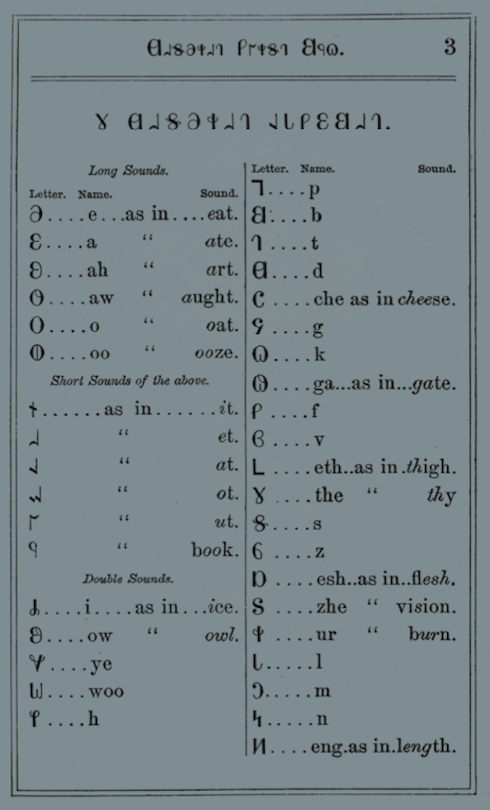

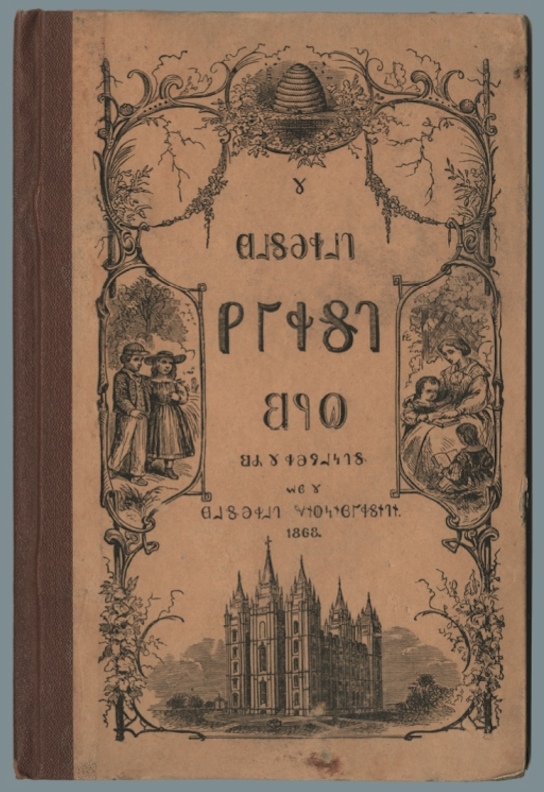

[The Deseret

First Book],

1868

Patricia D. Klingenstein Library, New-York

Historical Society

The Deseret Alphabet

Scholars at the newly

established University of Deseret (later Utah) attempted to aid non-English

speaking converts by offering a phonemic, or sound-based, spelling system

called the “Deseret Alphabet.” This instructional booklet was printed during

the alphabet's brief period of popularity.

The alphabet’s principal

inventor, a British convert, wrote admiringly of the Cherokee linguist Sequoyah

who invented an alphabet on the same principle decades earlier. (Sequoyah’s syllabary is featured in the next section, Cherokee Nation Reunited)

Tabernacle under construction, Salt Lake City

Patricia D. Klingenstein Library, New-York

Historical Society

The Community

Over 60 members of Salt Lake

City’s 14th Ward Female Relief Society created this giant quilt in 1857. It

demonstrates the Latter-day Saint embrace of collective labor and individual

creativity. Although the quilters shared fabrics, no two squares are exactly

alike. Most signed or stitched their names below their appliqued motifs.

These women had already

produced clothing for Paiute converts, woven rag carpets for the Tabernacle,

and integrated an endless stream of newcomers into the territory. Some among

them had been part of the first Female Relief Society in Nauvoo.

As Salt Lake City blossomed

into a kind of oasis for migrants on the overland trail to California, the

Saints established close to 100 new settlements to the south, some focused on

farming, some on iron or cotton production. These tiny communities formed a

300-mile chain down the center of the territory.

14th Ward Album Quilt. Facsimile. Images of the quilt and short biographies of its makers can be found in Carol Holindrake Nielson’s book, The Salt Lake City 14th Ward Album Quilt, 1857 - Stories of the Relief Society Women and Their Quilt, University of Utah Press

The Album Quilt

Choosing the popular album

quilt style allowed the 14th Ward quilters to showcase their individual talents

and affirm their faith in mottoes stitched or inked on their squares. Notice

the varied representations of bees, beehives, and the American eagle alongside

the words “In Unity We Stand” and “In God Is Our Trust.”

A 14th Ward schoolteacher won

the quilt in a raffle. Years later, after the death of his wife, he cut the

quilt exactly in half in order to

share it with his two eldest daughters. (Note the cut line through the middle

of the quilt squares.) The daughters’ families retained their portions but lost

touch with each other. That changed not long ago when the wife of a descendant

rediscovered and rekindled the families’ quilt connection.

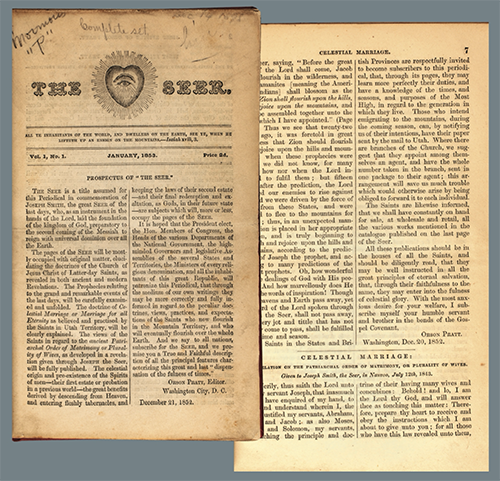

Orson Pratt

“Celestial Marriage,” The Seer, January 1853

Patricia D. Klingenstein Library, New-York

Historical Society

Conflict Over Plural Marriage

In 1852, Brigham Young openly

acknowledged the practice of plural marriage in Utah Territory. Although he and

a handful of other high Church officials became infamous for the number of

wives and children in their households, plural marriage was never the only, or

even the most common form of marriage. At its peak, the majority of polygamous

men had only two wives.

In 1856, a newly established

Republican Party denounced polygamy in Utah and slavery in the South as “twin

relics of barbarism.” The next year, President James Buchanan sent troops to

assert control of Utah Territory. As US forces advanced, Young organized the

evacuation of Salt Lake City and warned he would not allow the city to be

occupied.

Negotiations followed. Young

agreed to step down as governor and the army promised to remain outside the

city. “Buchanan’s Blunder” did nothing to end polygamy, but it did turn support

for plural marriage into a mark of loyalty to the Church.

In 1862, Congress passed an

anti-bigamy act, fueling efforts after the Civil War to control the religious practices

of the Saints.